Features

As Iran moves into the final week before two key elections, hardline media outlet Basij News Agency has made renewed calls to slow down internet speeds.

The Iranian electorate will go to the polls to elect members of parliament on February 26. Elections for the Assembly of Experts, one of Iran’s most influential governing bodies, take place on the same day. In what is undoubtedly a busy time for the Iranian public to exchange ideas and information online, the news agency, which is affiliated with the Basij paramilitary organization and the Revolutionary Guards, has emphasized the importance of developing Iran’s own intranet, and of keeping internet speeds down.

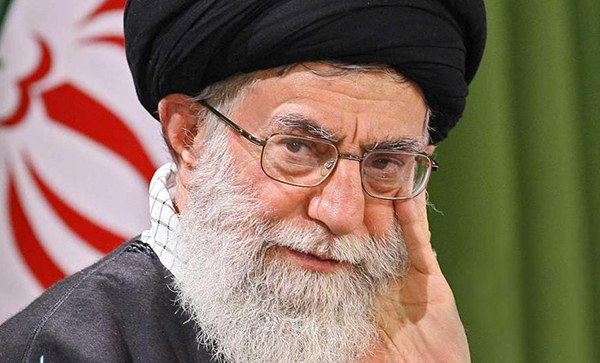

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei first ordered government officials to slow down internet speeds in 2012 until the country’s own “national information network and its satellite projects” were in place. This week, Basij News Agency reported that the order — issued on February 26, 2012 — was still in place. It reminded the Iranian public that Ayatollah Khamenei saw slower internet speeds as part of a tactic to stem the “spread of lies,” adding that any “internet connection that exceeds 128 kilobytes per second is absolutely illegal”.

The agency went on to say that anybody setting out to violate this order was directly acting against the orders of the Supreme Leader — implicitly accusing the moderate President Hassan Rouhani’s administration of the criminal offence. The claim echoed similar accusations made by Ahmad Elmolhoda, Mashhad’s Friday Prayers Leader, in September 2015, who directly accused the government of violating the ayatollah’s orders.

The Basij report quoted Mohammad Kahvand, an internet expert who said that the original order had coincided with the creation of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace. The role of the council, said Khamenei, was to combat “enemies of the revolution and Islam” and to support the “the Islamic cultural revolution.”

In the past, critics of the Iranian government’s efforts to speed up internet speeds had focused primarily on the fact that it had not gone through formal channels to support its policy. By law, any cultural policy, product or enterprise must secure parliament’s stamp of approval — a “cultural appendix” that verifies its value.

In spring 2015, parliament summoned Minister of Communication and Information Technology Mohammad Vaezi to answer questions on the issue. “Why is the Ministry of Communication expanding the internet and its bandwidth without a cultural appendix and before the national information network is launched?” hardliner MPs asked.

MPs were not satisfied with Vaezi’s response, giving him a “yellow card” for his unsatisfactory answers. But the minister shrugged it off. “We are not going to stop expanding internet bandwidth because of some nitpicking,” Vaezi said. Later that year, on November 6, he announced that the government was pleased with its progress, and reported that 25,000 villages would soon enjoy high-speed internet.

But although Khamenei and hardliners talk about a “national information network” — a concept more commonly known as the National Internet that has aroused considerable interest in international media — what do they mean, and how far along is the initiative?

Former conservative president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s administration originally set out plans for Iran’s “halal” internet on March 21, 2011, part of something an umbrella project called “the Fifth Development Plan of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

The plans were ambitious, stipulating that the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology would develop a network that would be up and running in two years, initially prioritizing access for government departments and state-run institutions, and then broadening out to serve 60 percent of Iranian households and private businesses.

Current communications minister Vaezi is among the project’s critics. He points out that the scheme goes back much further than the early days of the implementation of the Fifth Development Plan. On April 14, 2015, Vaezi told parliament that the idea goes back 12 years. “But as of today, nothing has been done about it, ” he said.

The “PowerPoint” Phase

According to hardline newspaper Vatan-e Emrooz, between 2006 and 2014, government departments spent the equivalent of around US$300 million on the national information network. In 2014-2015, about $400 million was earmarked for the project, and budget forecasts for the year 2015-2016 predict the same.

But the newspaper pointed out that the project is still in what it described as the “slideshow and PowerPoint” phase, and the Ministry of Communications has announced that it needs close to $2 billion to finish the project.

Nasrollah Pazhmanfar, a hardliner MP and a former member of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, said the government expects the project to be completed within 11 years — figures that fly in the face of statements issued during the end of Ahmadinejad’s presidency, which boasted that the project was 90 percent complete.

“At this moment the Iranian people are captive and entertained by a cyberspace that is in the hands of the United States,” wrote Pazhmanfar, casting the “non-Iranian internet” as part of a larger project to sabotage Iran’s efforts to uphold Islamic values and culture online — and clearly outlining the Rouhani government’s role in this. “Foreign media are working to promote fear among the Iranian people about the massive project of launching the national information network. By their repeated and widespread propaganda, they present the national information network as limiting access to the world’s network. Unfortunately the Ministry of Communications views the question in the same way. They also believe that this project is too big and impossible to do.”

Authorities are all too aware of the Iranian public’s internet habits and the fact that they are entering a second decade of not only taking control of what they access online, but also playing a vital role in disseminating information, news and opinion online — whether it’s gossip and fashion tips, news or debating international and domestic politics. Comments like Pazhmanfar’s remind the Iranian electorate that hopes to control these spaces are alive and well. The Iranian regime is unlikely to let go of its vision for a halal internet any time soon, and plenty of media pundits are willing to put their weight behind this vision.