Features

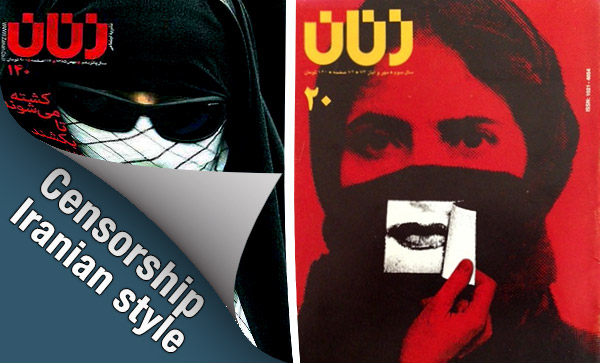

Journalism is a hazardous profession in Iran, and it can be even more dangerous when trying to report the truth about the government and Iran’s establishment figures. Censorship, Iranian Style is a collection of stories by 18 Iranian journalists, writers and cartoonists who have experienced censorship — under the Islamic government, as well as under the Shah’s regime prior to the 1979 Revolution. Their tales of being silenced, harassed and imprisoned provide a solid understanding of the everyday bravery and courage of Iranian journalists, and give a new perspective on the menacing and warped mentality of Iranian censor officials.

***

On February 7, 2008, Fars News Agency reported that authorities had banned the magazine Zanan (“Women”) for “insulting” the Basij paramilitary force. It was bad enough that the magazine I had loved and published my best work in had been banned, but even worse still was that it had been shut down for a story I wrote.

I knew that the charges against my story were just a pretext to kill the magazine, but still, in those days, I wanted to be wrapped in a blanket and dispatched somewhere far away, like a package smuggled across the border without anybody looking or suspecting. Even the mention that that rape story had been my work embarrassed me, and when people talked about the ban without mentioning me I felt happier and lighter.

Two years later, when I was leaving Iran in January 2010, I had packed some issues of Zanan in my suitcase. I left Tehran for Vienna and after three and a half months I was going to fly to my final destination, the United States. The airline permitted only two 23-kilo suitcases of luggage, and I put the copies of the magazine at the bottom of one suitcase and laid my clothes on top.

When the time came to weigh my baggage, the airline employee pointed gravely to one of the suitcases and said that it was overweight. I was impatient with lack of sleep and anxiety about my journey, and I just wanted to get away from the counter as soon as possible. I opened the suitcase, lifted a bunch of jeans and other stuff from the top, and threw them into the garbage can nearby. Back on the scale my suitcase was now just 21 kilos, and the man said I could return some of my things, I had lightened it too much. But I couldn’t be bothered to reopen the suitcase, drag the stuff out of the trash can and repack. I just wanted to check in my bags, shed their weight and get out of that line as soon as possible.

A few days after arriving in the United States, when the fog of jetlag lifted, I began to unpack, and discovered I had thrown out two issues of the magazine into that Vienna trash can.

Ever since, the feeling creeps up on me that I’m hidden somewhere in that trash can. I constantly stand up and shake myself but then get tired and fall back among the rubbish. I cannot jump high enough to get out of the can. I want to, but cannot. I have been left next to a bunch of other throwaways. I do not like to say that I am a throwaway, but this is the truth. I am next to a bunch of cigarette butts, papers, greasy plates and food leftovers; things nobody looks at any longer. But I believe that history has to begin or end somewhere around here. It cannot just avoid coming here, and until then I plot how I will get out. I think I will conserve my energy. I think some day someone will kick over the can or the municipality will take it and empty it out somewhere out of town. It is bound to happen this way.

Eight years after the fact, somewhere far from Iran, I sit now writing about those days. The magazine published my fateful story in spring of 2007; it was called “Three Men, a Woman and that Dark Night in the Meadows.” The story contains a strange irony. Even if the woman’s rape claim was not rejected by the court and the judge had found the men guilty of rape, under Islamic penal law all three of them would have been condemned to death. The report mimicked the tragedy itself. Either way it was a messenger of doom and death.

It was a spring day in 2007; we were sitting in the magazine’s offices, located on the second floor of a beautiful dead-end alley off Haft-e Tir Avenue. The sun flooded the space with light. The social affairs editor told me that a lawyer had contacted the magazine and asked for a reporter to attend his client’s court appearance. His client was a woman who has been raped. “Will you go?”

Of all the reporters at the magazine she had asked me. Perhaps she thought I would be enthusiastic. I had written before about other unpleasant subjects, from women’s self-immolation to the murder of an eight-year-old girl by her father. It was a pretty safe bet I’d agree to cover a rape case. The trial was up north, near the Caspian Sea, and I agreed to go – the magazine would pay the expenses, I would be away from Tehran for a while, on the coast and, of course, the subject was interesting.

I had never met a rape victim before. And I’d never met a woman who had shaken off her wounds and her anger and dared to talk about her experience before the police and a court of law. But I wasn’t sure whether I should praise her courage or pull her into a corner and whisper into her ear, “Hey, go back home, back to your husband. These people are not going to do anything for you.” If I had known her, I’d have certainly told her these things. I would have insisted that she remain silent so that she would not lose the little she had left. When in Iran had a raped woman voluntarily complained to the police and received justice? This only happened in Hollywood movies, not in northern Iran.

The court convened on a June morning. Her lawyer and I met outside the main gate of Lahijan’s Justice Bureau. After exchanging pleasantries, he introduced the woman next to him as his client, the same one who had recently been raped and for whose sake we had all gathered outside the Justice Bureau. I vaguely remember her clad in chador, tall and sturdy. I remember nothing about her face or the face of her lawyer. I remember nothing of the three accused men, only that the three of them sat next to each other on a bench in the corridor outside the court. Among all those characters, the only face I remember is one of the accused men’s father, who sat on the stairs and repeatedly told me, “They’ve done nothing. They’re the best boys in Lahijan.”

The woman was 27 and married. Unlike many other women who are raped in Iran, she had not wanted to remain silent from the start. Two days after the incident she went to the neighborhood police station, gave all the information necessary to open a rape case, identified the assailants, hired a lawyer and demanded legal justice. But during all that time, she had said nothing to her husband, to avoid endangering her marriage. I asked her outside the court why she had said nothing to him. “If I talk about it, my life will be in danger,” she said. “I wear a long-sleeve shirt at home to hide the bruises.” What she didn’t know was that from the moment that she filed her complaint, she had put her life at the edge of a precipice.

In the second session of the trial, the judge summoned the husband to appear in court. The night before going to court, the woman told her husband everything. The next day in the small courtroom he saw the three men who had raped his wife and learned more from their confessions.

A while later, as I was preparing the final report, I called the husband. I remember his low and trembling voice to this day. “Do you still love your wife?” I asked. “We have to suffer and live with it,” he said. I asked the same question in different variations, but could not get a straight answer. I asked him if he was thinking of getting a divorce. “I don’t know,” he replied calmly.

Later the woman told me that after her husband had appeared in court, his behavior towards her had changed. He refused to eat her cooking, would not sleep in their bed, did not talk to her and came home late at night. I can still hear her sobbing voice, “I think he is going to divorce me.”

I stayed in touch with the woman’s lawyer throughout, and he told the judge would probably reject her complaint and free the three defendants. After my story came out in the next issue of the newspaper, I could get no news from any of them – not the woman, not the lawyer, not the husband and not even from the attorney for the three defendants. None of them answered their phones or perhaps the numbers had changed. I have no idea why all of them cut contact entirely.

As was practice at the magazine, I read my story aloud on a Monday morning to the editorial board. The features group approved. Of all the people seated around the editor-in-chief’s large round table that day, only one suggested if it wouldn’t better to remove the mention of “Basiji” from the story. She was adamant that using that word might lead to trouble but others disagreed. The story kept in the word “Basiji” with the approval of the majority and was sent to the printer’s along with other material for that issue. My work was done after that. Now the magazine owned the story and I had to prepare for my next subject.

Sometimes I miss myself, the persona I was during the heyday of the magazine Zanan. I miss that big round table in the office of our editor-in-chief, Shahla Sherkat, and how the sun cast its rays into the middle of the room. We were young and enthusiastic journalists in those days, whispering together, reading our stories aloud. We thought we were important people doing important things. I have not had that feeling for a long time. It is as though that feeling belonged exclusively to that white building in the dead-end off Tir Avenue. I’ve stayed a journalist because I don’t know how to do anything else in this world. This is how I know how to make a living. But I have never had the same experience that I had with those colleagues, who read and understood the work properly, with profound attention. Zanan was a unique experience.

Sometimes I think of that 27-year-old woman, the rape victim. What is she doing now? Has she married again? Has she left that town? Has she by chance met any of those three men? If so, has she talked to them? How many times has she imagined killing them by her own hands? She must be around 35 now.

Since then, whenever I write about a banned magazine or a newspaper, the first question that comes to mind is which reporter or cartoonist is responsible. I imagine him or her walking the hallways of the newspaper moments after learning that the paper has been banned. How does she react when she faces her colleagues? Does she feel pangs of conscience?

After so many years when I read the news about people who have been executed on charges of rape, I look for the place, the date and their names because the reports identify them by the initials. But none of them date to 2008. It is a strange feeling. I detest the death penalty but by pursuing and reading these stories, I am somehow searching for death, the death of those three men. This goes completely against what I have been doing in recent years.

Today I am working with a human rights organization in the United States. One of our main activities is fighting the death penalty and violations of human rights in Iran. In the past few years I have written numerous reports criticizing the use of capital punishment on charges such as “corruption on earth”, “drug smuggling” and “forcible rape.” But to be honest, I still wish that the complaint by that 27-year-old woman had not been rejected, even if it had resulted in the execution of those three. It is not my fault that the punishment for forcible rape, under the Islamic Republic of Iran’s interpretation of sharia law, is death. It could have been something else like a prison sentence. In that case, perhaps those three would now be serving time, and although the woman would have lost a great deal, at least she would have felt some comfort in knowing something had been done.

Eight years later, on the morning of April 27, 2015, in another continent and in the heart of the United States, I read on Facebook that the magazine Zanan-e Emrouz (“Women of Today”) had been shut down after 12 issues. A short while later, I interviewed its managing editor, Shahla Sherkat, on the phone. I did not know what to ask from across the world, except insipid questions like: why was it banned and have you received the ruling? I told her, “I’m sorry that your magazine has been banned again.” That was all.

This time, Fars News Agency reported that the authorities had banned the magazine for promoting “white marriage,” or cohabitation. In recent years it has become easier to write about rape or to file rape complaints, but apparently now it is a difficult time to write about couples who live together without exchanging vows. In my Iran even banning publications has become a frequent and ordinary affair, just like natural calamities – like a flood that washes away everything on its path. Zanan has been banned again. This time because of someone else’s story. I feel like crying in another corner of the world. I’m wondering whether something magnificent might still remain amidst so much destruction, repetition and sorrow.

More stories in this series:

“I could not document history”, by Hasan Sarbakhshian

The Seven Obstacles to Publishing Books in Iran, by Ebrahim Nabavi

All Beards Are Sacred, by Touka Neyestani

The Working Journalist in an Atmosphere of Terror, by Isa Saharkhiz

The Midnight Watch, by Ehsan Mehrabi

Censorship, As Ordinary as Breathing, by Mana Nayestani

The Tragicomedy of Censorship in Iran, by Masoud Behnoud

The Islamic Sex-Ed Calendar, by Reza Haghighatnejad

Stories from Students’ Protests, by Siamak Ghaderi

My Husband Was a Tasty Morsel for the Regime, by Mehrangiz Kar