Features

The end of the Second World War signaled the beginning of an information war in Europe. As the military alliance between the Soviet Union and its main western allies — the United States and Britain — came to an end, the USSR backed small communist parties that asserted ever-tighter control over much of Eastern Europe.

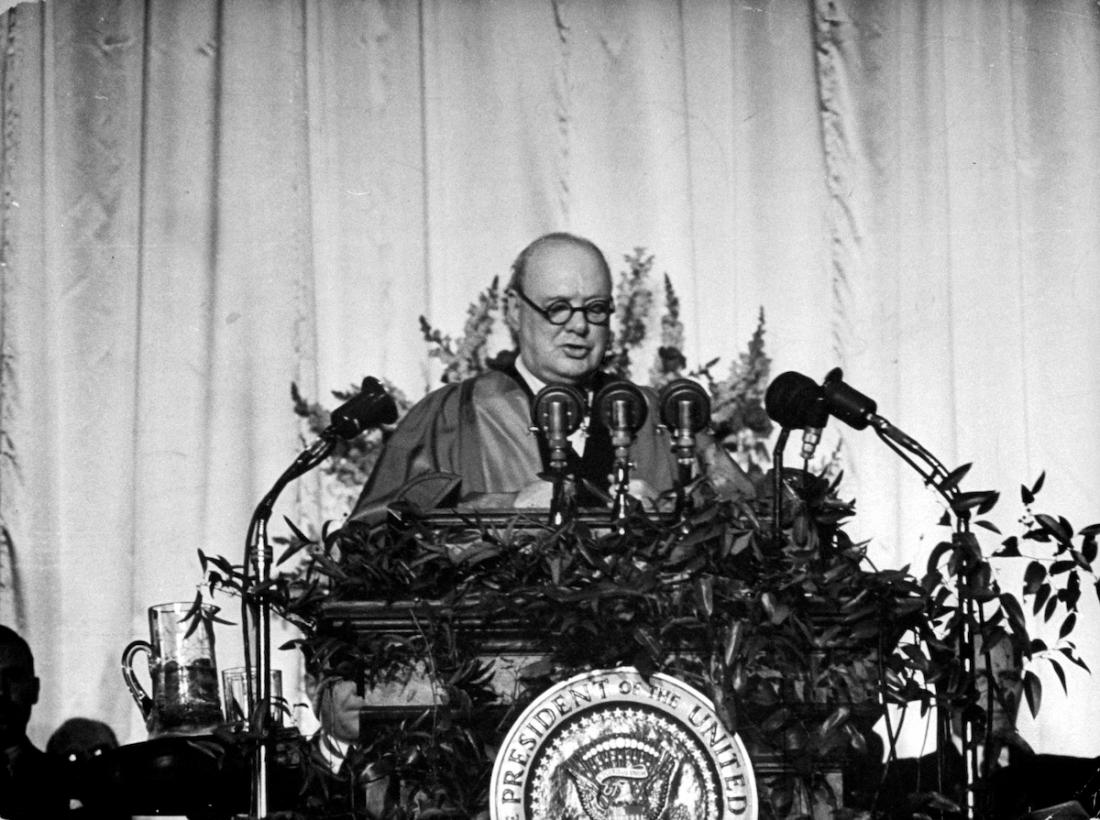

Speaking in Fulton, Missouri in March 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill warned of an “Iron Curtain” of totalitarian control sealing off half the continent. His speech heralded the beginning of an ideological “cold war” that would last for more than 40 years, a struggle in which citizens of the eastern camp were only meant to hear one side of the argument.

“We talk about the Iron Curtain as a physical barrier, but it was also an information curtain,” says A. Ross Johnson, a former director of Radio Free Europe and author of a history of RFE and its companion station, Radio Liberty, which broadcast into the Soviet Union. “All the communist regimes saw control of information as a key to their rule.”

Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivers his "Iron Curtain" speech in Fulton, Missouri

The new communist states — of which only Czechoslovakia held out for a short time as a semi-democracy — controlled all media within their borders and used customs controls to keep out western books and periodicals. “It was rational self-interest from their point of view,” Johnson says. “They understood that independent information and alternative viewpoints were a threat to their rule.”

As refugees poured out of Soviet-controlled countries, American intelligence officials including Frank Wisner, the director of the Office of Strategic Services (a precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency) and Allen Dulles, the future Director of Central Intelligence, along with State Department officials George Kennan and Joseph Grew, saw an opportunity to put émigrés to work as American propagandists.

In 1949, Dulles and a group of prominent Americans —notably former allied commander and future president General Dwight D. Eisenhower and film director Cecil B. DeMille — established the anti-communist National Committee (NCFE) for a Free Europe to spread America’s message in the East. The NCFE took a special interest in the one medium the communist regimes could not fully control: the airwaves.

From “Fake News” to Full Service Substitute

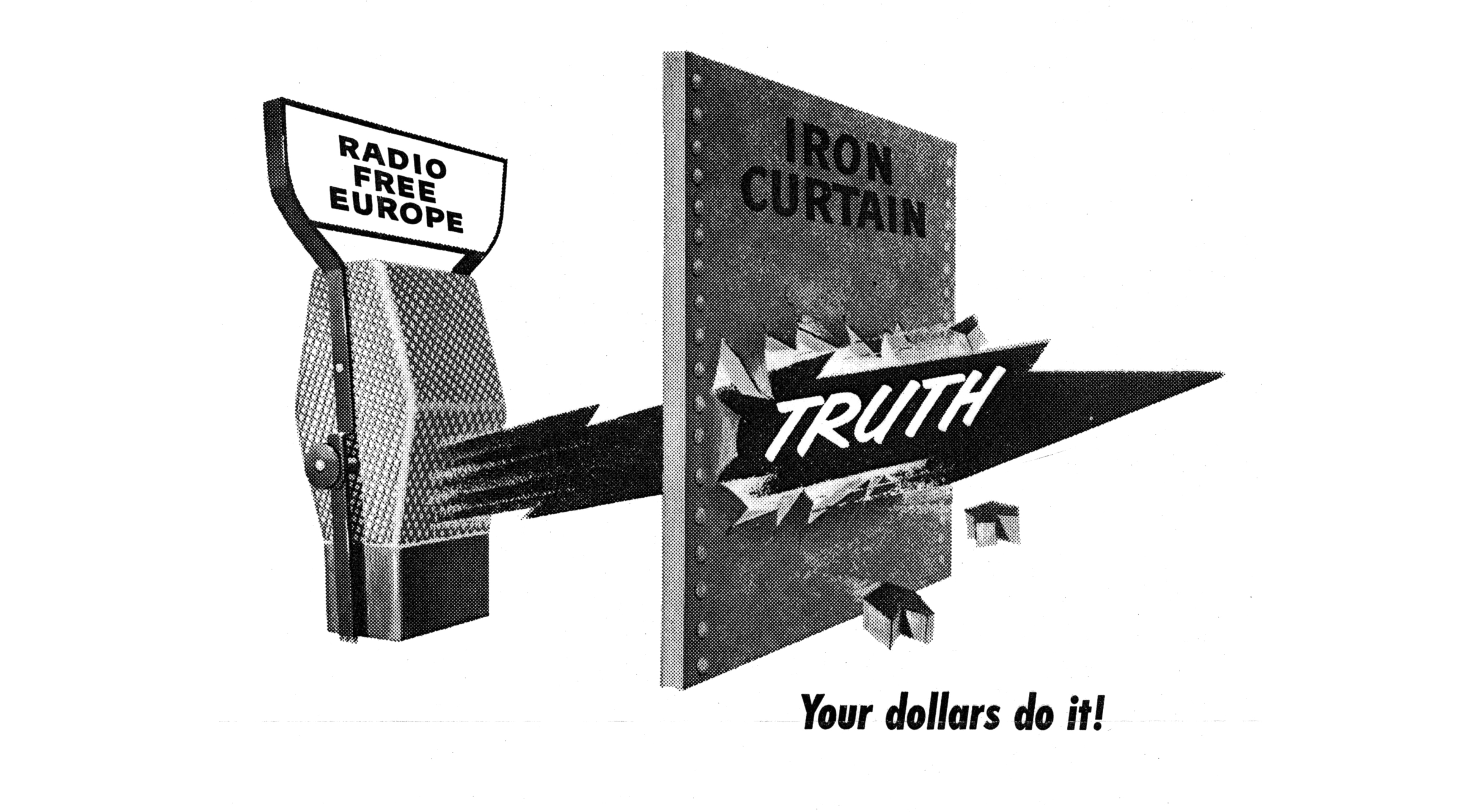

The NCFE’s central aim was to put talented émigrés from the Soviet sphere on the air in their own languages to promote an anti-Soviet message behind the Iron Curtain. In 1950, an organization known as the Crusade for Freedom launched a funding drive for the NCFE. Eisenhower, then one of the most popular men in the United States, promised that the new radio stations would have “the clearest, simplest charter in the world: tell the truth.” Yet while the NCFE presented itself as a private organization of freedom-lovers and its campaign raised over a million dollars, it ultimately received most of its funding from the US Congress through the newly-established Central Intelligence Agency.

A fundraising advertisement for the Crusade for Freedom

A fundraising advertisement for the Crusade for Freedom

Radio Free Europe set up its first transmitter, which had belonged to the US Office of Strategic Services, near Frankfurt in West Germany in 1950. On July 4 that year, it presented its first broadcast to Czechoslovakia. That was followed by broadcasts to Romania, Hungary, Poland and Bulgaria.

Soon, RFE was broadcasting from a more elaborate setup in Munich, which gave it some distance from old OSS spymasters, and would remain its main base until the end of the Cold War. But gaining credibility in the East proved a slow process.

“During the first broadcasts, they really didn't know what they were doing,” says Richard H. Cummings, a historian of Cold War Radio who worked as the director of security for Radio Free Europe in Munich in the 1980s. “It was all hit and miss. They didn’t care. They were just putting something out there. I would say it was propaganda. You could call it ‘fake news.’”

“During the first couple of years, they were trying to find their way,” Johnson says. “Up until about 1953, you’ve got some real propagandistic ideas, even thoughts of stirring up trouble, naming names, naming and shaming suspected communists at the local village or factory level, often without any evidence. But they quickly realized that that was not useful or productive, because that was not what people in the east wanted.”

But within the first few years, Johnson says, the organization began to develop a more responsible and ambitious outlook. As early as 1952, he says, policy advisor William Griffith had argued that RFE should provide a “full service substitute” for censored domestic media across the Soviet sphere.

“He said the aim of Radio Free Europe was to be what Radio Budapest or Radio Prague would be if they could be free. In those days, full service radio meant everything from hourly newscasts to cultural programs, religious programs, music, to political commentaries and political programs.”

To see how audiences were reacting, RFE began a program of interviewing refugees and travelers from the east.

The year 1953, Johnson says, marked a turning point for the organization, not least because it had a major story to cover. That June, Soviet forces cracked down on workers’ demonstrations across East Germany, leaving little doubt that Moscow would crush any popular movement behind the Iron Curtain.

“After that, you see very quickly a move toward more responsible, fact-based journalism, which was driven from below by the editors and the American managers at RFE.” Those RFE staff, he says, often argued successfully with the passionately anti-communist policy makers and leaders of the NCFE, some of whom continued to push for more aggressive tactics.

An Early Success, an Early Failure

The following year, RFE scored a major scoop when Józef Światło, a notorious high-ranking official in Poland’s secret police, defected to the West and revealed state secrets which, when broadcast back to Poland, demoralized and destroyed parts of the secret police apparatus. “It was a series of broadcasts over several months,” Johnson says, “and it had a concrete effect. People lost their jobs. Departments were discontinued.”

But there was a major journalistic controversy to come. In October 1956, when Hungarians took part in a mass uprising against communist rule, RFE’s Hungarian service responded in ecstatic, sometimes aggressive tones, even offering tactical advice that some listeners took as a sign that they could rely on the US to back their revolution.

“This was the granddaddy of RFE mistakes,” says Malcolm Byrne of the National Security Archive at George Washington University. “Many Hungarians, and critics generally, saw that as a cynical move by Washington, which seemed to show a willingness to sacrifice Hungarian freedom fighters for the sake of Cold War objectives.”

In 1956, the Soviet Union sent tanks to crush a revolution in Hungary

Later investigations, he says, show that the main fault lay with a handful of Hungarian-language broadcasters who took it on themselves, in the heat of the moment, to try to raise their countrymen to action.

But ultimately, the broadcasts were a US responsibility. “RFE management deserved blame, too, for not having any Hungarian speakers among that section’s supervisors, so they apparently had no idea what was being broadcast.”

Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev sent the Red Army to crush the uprising. More than 2,500 Hungarians were killed, and 200,000 fled west as refugees.

“Suddenly, there was shock in Washington, the idea that maybe we had gone too far this time,” Cummings says. “After that, RFE had to work to get the listeners back.”

The View from the Other Side of the Curtain

Petr Brod is a journalist who worked for RFE’s Czechoslovak service from 1987 to 1993. He was born in 1951, just three years after the full communist takeover in his country. While the Czechoslovak media remained relatively free for a time after the war, he says, they had observed an unspoken consensus that, since the Soviet Union had liberated the country from Nazi occupation, the media should not harm Soviet interests.

But by 1948, he says, they would have little choice in the matter. “That year, all the media were put under the surveillance of the communist party. There were no private media to speak of, no private newspapers, no private radio stations, and everything was nationalized.”

Brod remembers listening to RFE with his parents in Czechoslovakia, although it wasn’t easy. “The experience was very limited by the strong jamming,” he says. “Until the beginning of the 60s, even the BBC European Service was being jammed. This also applied to the Voice of America and other western stations. It was very difficult to listen to RFE in the larger towns, which were the main target of the domestic jamming transmitters.”

But in the countryside, he says, jamming was weaker and many people went to their dachas for the weekends so they could listen to foreign broadcasts.

Asked to describe what the jamming sounded like, Brod imitates the noise: “Woooo Woooo Woooo Woooo Woooo.”

In 1968, Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev sent tanks to crush the “Prague Spring,” a reformist movement led by the popular Czechoslovak communist leader Alexander Dubček. The following year, Brod and his parents moved to Munich, West Germany, where RFE was based. Brod, then 17, could finally hear the signal loud and clear.

East German troops close the border with West Berlin ahead of construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961

“Listening to those programs was one of the main ways of staying up to date with developments in my country,” he says. “I was very grateful for the comments by experienced journalists who mostly belonged to two waves of emigration: there were the ‘48ers who had fled just after the communist takeover and the ‘68ers who had fled from the Soviet invasion. I mostly listened to the flagship program, which was broadcast at 10 past six in the evening. It was an hour of commentary on events in Czechoslovakia and the world.”

In the 1960s, US foreign policy — especially the war in Vietnam — had turned many young people in the West against the US. But Brod, like so many of his contemporaries from the communist sphere, had a more heroic image of the country behind RFE.

“After my experience with Soviet policies, I was very pro-American,” he says. “I thought that America was the ultimate guarantor for the existence of democracy and freedom in the world. It was also the power that was responsible for the safety of Western Europe from Soviet attack. And I knew that just like myself, many Czechs and Slovaks, despite being forced to express their loyalty to the Soviet Union, were in fact very pro-western and pro-American.”

The Enduring Specter of the CIA

In 1967, a scandal surrounding the exposure of covert CIA funding for the foreign activities of the National Students Association — an alliance of student governments based on US college campuses — led to widespread US media investigations of CIA-funded programs. While the CIA had seen its funding as a way to counter communist-funded student groups, those investigations led to new restrictions on what types of organizations the CIA could fund.

While RFE and Radio Liberty were initially exempted — and their policy guidelines, in any case, came from the State Department — CIA funding ended in 1971. From that point on, RFE and RL were to be funded by Congressional appropriation through the Board for International Broadcasting. The two radios merged in 1976. But the controversial legacy of CIA funding would remain useful to communist governments for decades to come.

The Soviet Union sent tanks to crush the "Prague Spring" in 1968

Cummings, who worked as RFE’s director of security in Munich from 1980 to 1995, remembers how the CIA legacy played out. “In my time, there was no CIA influence. The CIA had been told to get out, and CIA people were not allowed in the building for any reason.”

But in the state-controlled media of the Eastern Bloc, RFE’s CIA history remained a recurring theme. “I was identified as being CIA, although I never was,” Cummings says. “They would always go back to the 1950s, showing that the CIA was there and here is the evidence. And it was true, nobody could deny that. But they never talked about how the CIA had been forced to leave and could no longer finance RFE.”

Eastern Bloc state media pursued a vigorous propaganda campaign against their rival. “There was an interesting dialogue that was taking place between RFE and Radio Moscow and Radio Prague,” Cummings says. “We would say something, they would say something. You had a major network of propagandists in Eastern Europe whose task was to counter the Radio Free Europe message.”

And in some cases, Eastern Bloc spies penetrated the organization and then crossed the Iron Curtain to attack it in state media. “They had people who had infiltrated RFE. They wanted re-defectors, people who could say, I worked for RFE for 15, 20 years, and this is what they do, these are CIA people, and so on.”

Agents and supporters of the Eastern Bloc governments, regarding RFE as a facet of enemy intelligence, also targeted the organization through violence, carrying out abductions and murder attempts against RFE staff.

In one sensational 1978 case, an assailant murdered the Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov with a poison-tipped umbrella on Waterloo Bridge in London.

In February 1981, terrorists under the command of Ilyich Ramirez Sanchez, AKA Carlos the Jackal, bombed the RFE headquarters in Munich causing injuries but no deaths. Investigations revealed that Romanian dictator Nicolai Ceausescu had funded the attack.

“The 1980s were a very interesting time,” Cummings says. “Sometimes I didn’t know if I was going to get through the day.”

The "death strip" dividing East and West Berlin. Anyone attempting to cross would be shot by the East German guards. Photo: George Louis at English Wikipedia

The Radio Free Europe building in Munich following the February 1981 bombing

The Collapse of the Eastern Bloc

The Soviet-backed regimes would not survive the decade. Undermined by Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev’s abandonment in 1988 of the “Brezhnev Doctrine” — the policy of military intervention in Eastern Europe — the East European regimes could no longer sustain themselves.

In February 1989, the Polish labor union Solidarity held negotiations with the Polish government, bringing to office Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Eastern Europe’s first non-communist prime minister.

In May, Hungary began to dismantle its border with Austria, allowing many East German refugees to flee to the West.

In October, East German General Secretary Erich Honecker was forced to resign.

In November, major protests began in Prague. By December, a non-communist government had taken power in Czechoslovakia, and voters had elected the dissident playwright Vaclav Havel president in a non-violent transition of power known as the “Velvet Revolution.”

Events did not progress as smoothly in Romania, where dictator Nikolae Ceausescu ordered the shooting of demonstrators before fleeing Bucharest. When a military unit captured Ceausescu and his wife in the countryside, they held a mock trial and shot both of them.

“Everyone was surprised by how quickly these regimes collapsed in the end,” Johnson says. “But if these regimes were going to disappear, then the concern was that that should be peaceful and non-violent. The miracle was that that there wasn’t any large-scale violence. The Mission of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty was to promote gradual change, but the logic of that was that if you keep changing gradually, you eventually get to the point where the system is completely different.”

Berliners tear down the wall

Czech dissident Vaclav Havel became president of Czechoslovakia at the end of 1989

Since the collapse, Johnson says, RFE’s efforts received wide acknowledgement, not only from opposition figures like Vaclav Havel and Polish Solidarity leader Lech Walesa, but also from Eastern Bloc intelligence officials like the East German spymaster Marcus Wolf.

“RFE was acknowledged both by the victors of the revolution and by those who lost their power,” Brod says. “Western media were not only the dissidents' lifeline to the West and to free information, but also a lifeline to many people from the ‘grey zone’ so to speak, people who were not openly committed to the struggle against communism but who were also to not followers of the regime, which was probably the largest part of the population.”

And, as elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc, the communists were listening, too.

“One extreme example was Vasil Bilak,” Brod says, referring to the man who was second-in-command in the Czechoslovak Communist Party. “When somebody asked him how he had learned about the events of November 1989, he replied, ‘By listening to RFE of course.’”

Today, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty broadcast into 23 countries where they deem the media unfree, including Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Russia.