Features

Nearly two decades before Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev brought the Russian word glasnost, or “transparency,” into official Soviet politics in 1986, a small group of dissidents risked intimidation, arrest, imprisonment, and exile by editing and circulating a secret, typewritten periodical holding Soviet political and legal impunity up to constant scrutiny.

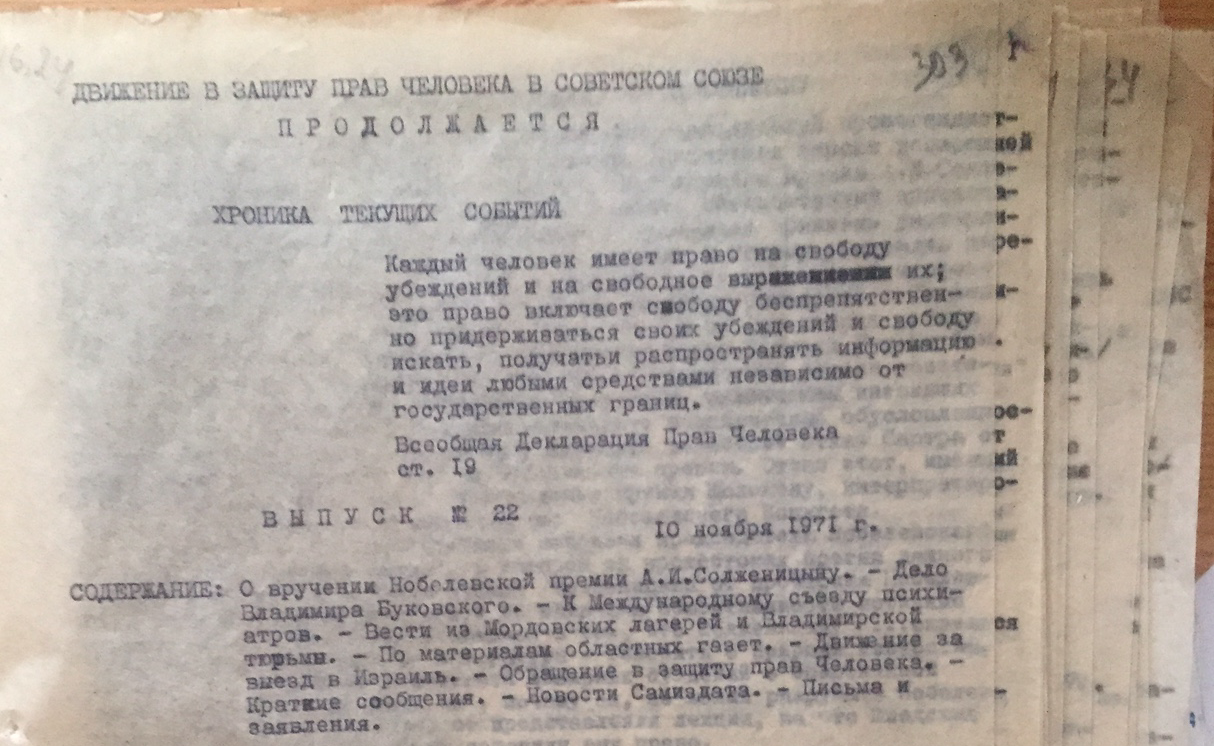

Launched in 1968 to mark the 20th anniversary of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Chronicle of Current Events (which was originally titled Human Rights Year in the Soviet Union) published accurate accounts of hundreds of political trials and human rights abuses and detailed the Soviet judiciary’s violations of Soviet laws and the Soviet Constitution.

“There just came a moment when society needed something like that,” says John Crowfoot of Rights in Russia, a researcher and translator who has gathered all the translations of the Chronicle on an English language website. “There had always been a tradition of passing secret documents around going back to the 19th century. In the Soviet Union, if you had a typewriter, you could make six copies at once using carbon paper. Someone would retype a document they had received and pass it on.”

The Russian word samizdat, the term used to describe such secret publications, is a portmanteau of sam, or “self,” and izdatel’stvo, or “publisher.” It entered common use in the 1960s. Early samizdat publications, says Martin Dewhirst, a Glasgow University lecturer who worked to prepare the Chronicle’s contents for broadcast on Radio Liberty during his university holidays in the 1970s, had mostly been devoted to banned poetry and other literature.

“It wasn’t until the mid-1960s that samizdat became more political,” Dewhirst says. One reason for this was the 1964 trial of the poet Joseph Brodsky. Brodsky was tried for “anti-Soviet” views and “social parasitism,” the latter charge pertaining to his claim that poetry was his profession.

Frida Vogdorova, a correspondent for Literaturnaya Gazeta, secretly took notes at the trial and circulated them. Brodsky was sentenced to work in a northern labor camp, although the sentence was commuted after 18 months as a result of international pressure.

Then, in 1966, the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel faced a high-profile trial for “anti-Soviet activity” over satires they had published abroad. Once again, people present at the trial took notes surreptitiously, which formed the basis for the White Book, a samizdat record of the trial. Both men were sentenced to hard labor in prison camps, for seven and five years, respectively.

“This was the first big trial, and it got the authorities worried because people protested in a way they had never protested before,” Crowfoot says. “Sinyavsky and Daniel refused to admit they were guilty. Two years later, the person who compiled the White Book was also put on trial.”

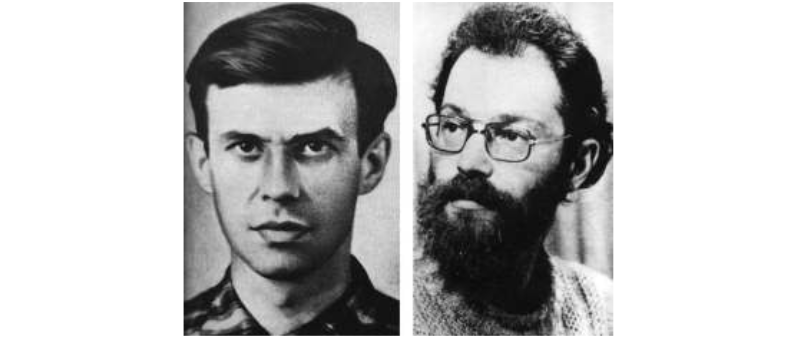

His name was Alexander Ginzburg. One of his co-defendants, who had assisted him with the book, was Yuri Galanskov. When they were arrested, they found supporters across the Soviet Union, who wrote petitions in their favor. But in 1968, both men were sentenced to five and seven years in the labor camps, respectively.

In 1972, Galanskov died as a result of medical neglect of his bleeding ulcers in a Mordovian prison camp. The Chronicle published the details surrounding his death.

Launching the Chronicle

The first edition of the Chronicle was dated April 30, 1968.

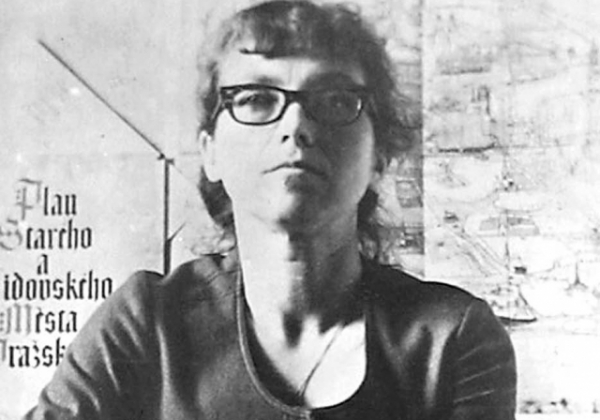

“The first editor of the chronicle, Natalia Gorbanevskaya, was an interesting, tough character,” Crowfoot says. “She was a literary specialist and a translator from Polish, and she could also type very well. She said the Chronicle should have two elements: it should have reports about what is happening that were written in very restrained, accurate language, and, she decided at the end of 1968, it should also give people an idea of what is circulating in samizdat, from fiction to political tracts to discussion of philosophical issues.

Natalia Gorbanevskaya, one of the first editors of the Chronicle

It also carried an appeal to the Budapest Conference on Communist and Workers’ Parties over the trials, and an account of the trial of a Christian political organization in Leningrad.

Although the people behind the Chronicle were not journalists in the western sense, they drew upon a network of sources throughout the Soviet Union who proved reliable and established a collective ethic that stood in contrast to the often exaggerated and emotional tone of the state-controlled Soviet press.

“A number of them were scientists,” Crowfoot says. “They were all established in their fields. They were biologists, mathematicians, and physicists. They had a very strong sense of objectivity. They wanted not to have any kind of pathos in what they reported even if the subject was tragic, and to be as accurate and dispassionate and informative as they could.”

Unlike ordinary newspaper and magazine editors, they dared not establish a formal editorial board or name themselves for fear of exposing themselves to the very dangers they were documenting.

Their message to readers was to pass the Chronicle on to people they trusted, but never to try and trace the chain back to the editors, lest they endanger the publication.

The first issue covered the five-day trial of Galanskov and Ginzburg along with two other people accused of “anti-Soviet” agitation, and detailed the repressive measures the state took against people protesting the trial

“Trust is an absolutely key factor of Russian society,” Dewhirst says. “Russia has always been a ‘low trust society.’ Soviet citizens, from birth, had to have an intuitive feeling that ‘Mr. A is absolutely trustworthy and Mr. B isn’t trustworthy.’ Natalia Gorbanevskaya was very finely attuned to the people she was dealing with and sensed whether someone was trustworthy enough not to spill the beans if that person was detained or arrested.”

Dangerous Work

The world could not ignore the Soviet Union in 1968. On August 20th that year, Soviet forces, along with forces from five Eastern European “Warsaw Pact” countries beholden to Moscow, invaded Czechoslovakia to crush the reformist “Prague Spring” movement and overthrow the popular Czech communist leader Alexander Dubček. The invasion caused international outrage and led many foreign communists to reconsider their allegiance to the Soviet Union.

Inside Russia, where state propaganda spun the invasion in Moscow’s favor and the cost of protesting was high, the response was muted. Nevertheless, Gorbanevskaya was one of eight protesters who gathered in Red Square to denounce the invasion. Gorbanevskaya had her three-month-old son with her, and, alone among the protesters, managed to escape immediate detention.

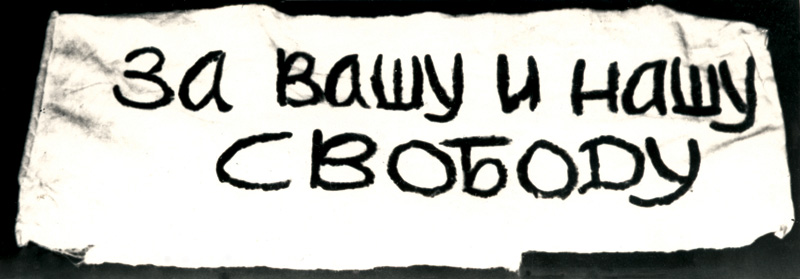

"For Your Freedom and Ours" banner carried at the 1968 Red Square demonstration against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Chronicle devoted its third issue, dated August 30th, to the invasion.

It included an open letter from Gorbanevskaya to the international press, describing the scene of the Moscow demonstration:

At midday we sat on the parapet at Place of Proclamation [in front of St Basil’s Cathedral] and unrolled banners with the slogans LONG LIVE FREE AND INDEPENDENT CZECHOSLOVAKIA (written in Czech), SHAME ON THE OCCUPIERS, HANDS OFF CZECHOSLOVAKIA, FOR YOUR FREEDOM AND OURS. Almost immediately a whistle blew and plainclothes KGB men rushed at us from all corners of the square. They ran up shouting ‘They’re all Jews!’ ‘Beat the anti-Sovietists!’ We sat quietly and did not resist.

The issue also reprinted a Samizdat pamphlet on the invasion entitled, Let Us Think for Ourselves. It provoked Russian readers to imagine a foreign communist invasion to alter the course of Soviet communism:

Supposing a few of our ardent heirs of Stalin or [Stalin’s secret policeman Lavrentiy] Beria suddenly decided to call on our Chinese, Albanian and other brothers to come to their aid? What if the tanks and parachutists of these brothers suddenly appeared during the night in the streets of our towns? And if their soldiers, in the name of rescuing and defending the ideals of communism — as they understand them — began to arrest the leaders of our Party and State, to close the newspapers, shut down the radio stations, and shoot those who dared to resist?

Gorbanevskaya was arrested the following year. In 1970, she was sent to a strict regime mental hospital in Kazan about 500 miles east of Moscow, in an attempt to discredit her. She was released in 1972 and emigrated to France in 1975.

“This was a threat to everyone working on samizdat,” Dewhirst says. “They might not be sent ‘merely’ to a labor colony or a prison, but they might be regarded as insane, because, as former General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev had said some years earlier, only somebody who was mad could be opposed to the Soviet regime.”

Several of Gorbanevskaya’s colleagues, Sergei Kovalev, Tatyana Velikanova, and Tatyana Khodorovich, kept the Chronicle going. Contents included early accounts of Soviet efforts to suppress the novels of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, coverage of Soviet abuses of psychiatry, and articles on the rights of ethnic and religious minorities. It continued to cover trials and the judiciary’s violations of Soviet law.

Typescript pages from the Chronicle. Typists could make six copies at once using carbon paper

“The ‘legalism’ followed by the Chronicle was very important,” Crowfoot says. “When you demand that officialdom and the authorities respect their own constitution and the international agreements to which they have signed up, you are putting them on the defensive.”

But in June 1972, the Committee for State Security, or KGB, arrested two of the Chronicle’s contributing editors, Petr Yakir and Viktor Krasin.

“Yakir and Krasin were threatened with the death penalty,” Dewhirst says. “They didn't want to be shot, and this threat, whether or not it was genuine, caused them to break down psychologically. This almost finished the dissident movement off in the early 1970s.”

The Chronicle did not publish another edition until 1974. That year, Kovalev, Velikanova, and Khodorovich gave up their anonymity and held a press conference where they openly distributed several issues of the Chronicle to the foreign press.

The following year, Kovalev was arrested and sentenced to seven years in a labor camp. Khodorovich fled the country. Velikanova was arrested in 1979 and sentenced to five years in a labor camp and five years of internal exile.

Persecution of the Chronicle’s editors continued into the early 1980s. The 64th issue, dated June 30 1982, was the last to circulate. A 65th issue was prepared but never released. Its last editor, Yuri Shikanovich, was arrested in November 1983.

After 15 years, the Chronicle, and much of the dissident movement, had been crushed.

Remembering the Chronicle

Vera Chalidze was a young woman in her twenties living in Moscow when the Chronicle and other samizdat publications were circulating.

She had first discovered underground writing in the form of tamizdat, or underground texts from abroad (tam means “there” in Russian) through her parents. She had following the Sinyavsky-Daniel trial closely.

Chalidze’s cousin, Pavel Litvinov, was one of the eight protesters arrested in Red Square for demonstrating against the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. And while Chalidze knew Gorbanevskaya personally, and thought her a “truly wonderful poet and prose writer,” she did not know that Gorbanevskaya was the editor of the Chronicle.

Chalidze remembers reading and re-typing copies of the Chronicle in secret.

“For me, because I was young and sort of irresponsible, it was extremely exciting,” Chalidze says. “I was part of something dangerous, something banned. But it was also extremely informative.”

Whereas foreign Russian language radio stations like Radio Liberty and the BBC Russian Service were limited in their access to events taking place inside the country, she says, the Chronicle had reliable sources from the big cities to the provinces.

But like the editors, readers and circulators of the Chronicle were taking a big risk.

“The anxiety was pretty high if I was carrying it or passing it on to another person,” Chalidze says. “There was always fear that one was being followed by the KGB, and there was always a risk of putting somebody in danger. But for me, it was romantic. I am ashamed to say that I was really curious to know how I would take being imprisoned or sent to the camps. I had read about the camps, and in my naiveté, I was quite curious to experience it. I did it in part as an adventure.”

Issues of the Chronicle were regularly smuggled out of the Soviet Union for translation, likely through the diplomatic bags of western embassies or by travelers from Eastern Europe. And while the chronicle was only one of many Samizdat publications, those concerned with human rights in the Soviet Union were always keen to read what was widely regarded as the best among them.

Martin Dewhirst, a Royal Air Force-trained Russian language expert, often traveled from Munich to analyze and help prepare articles in the Chronicle for broadcast on the US-funded Russian language service, Radio Liberty.

“Whenever a new copy arrived, it immediately jumped to the top of the queue,” Dewhirst says. “We always had a backlog of samizdat, but the Chronicle was regarded as extremely reliable because it contained very few factual mistakes. Any mistakes that did appear were carefully corrected in a later issue so that the compilers and editors couldn't be accused in the Soviet press of being dishonest.”

So trusted was the Chronicle that, beginning in 1971, the human rights group Amnesty International began to publish issues of the Chronicle in English. Translator Peter Reddaway dedicated a 1972 collection, titled Uncensored Russia, "to the editors of the Chronicle, whose names are unknown to me."

Now, as the world debates a proliferation of “fake news” on social media, and traditional media outlets struggle to maintain high standards in the face of dwindling resources, the Chronicle stands as a model publication.

“They had extremely high journalistic standards,” Dewhirst says. “I'm amazed at how much lower standards are even in reputable newspapers published in London today. This was really very high quality stuff. The Chronicle was the best answer to Soviet lies and Soviet misrepresentation.”

Issues of the Chronicle of Current Events can be read in English at https://chronicleofcurrentevents.net