Features

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn began The Gulag Archipelago with one of the most searing passages in literature:

In 1949 some friends and I came upon a noteworthy news item in Nature, a magazine of the Academy of Sciences. It reported in tiny type that in the course of excavations on the Kolyma River a subterranean ice lens had been discovered which was actually a frozen stream — and in it were found frozen specimens of prehistoric fauna some tens of thousands of years old. Whether fish or salamander, these were preserved in so fresh a state, the scientific correspondent reported, that those present immediately broke open the ice encasing the specimens and devoured them with relish on the spot.

Few readers of that science journal, Solzhenitsyn observed, would have understood what sort of people rush to eat prehistoric creatures. But he and his friends had understood immediately, for they, too, had been zeks, the half-starved prisoners of the network of hundreds of forced labor camps spread across the world’s largest country like a string of islands. Each of those islands had been governed by the Soviet Union’s “Main Camp Administration,” whose Russian acronym was GULAG.

The “Standard Path”

Solzhenitsyn was born in 1918, a year after Lenin’s Bolsheviks seized power from Russia’s provisional government, which had taken power following the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in February 1917.

The Russian Civil War, in which the Bolsheviks struggled to resist overthrow from abroad and crush opposition at home, had formed the background of his early life.

When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, Solzhenitsyn joined in the Red Army and was decorated for his service. But in 1945, he was arrested for writing sarcastically about Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin in a private letter. Soviet authorities sentenced him to eight years in the camps. This move from the front line of the Second World War to the gulag, he later told the BBC, was a “standard path” for many young men of his generation.

Following the death of Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin in 1953, his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, denounced his former master’s paranoid and extremely repressive style of rule. In his 1956 “secret speech” to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev demanded that the Party reject Stalin’s “cult of personality.” The contents of the speech soon leaked, and the result was a political “thaw” whereby Soviet citizens, and Soviet writers, began cautiously to speak and write about their experiences during the Stalin years.

Solzhenitsyn, who had been released from the camps on March 5, 1953, the day of Stalin’s death, was to become the first writer living in the Soviet Union to write openly about the camps.

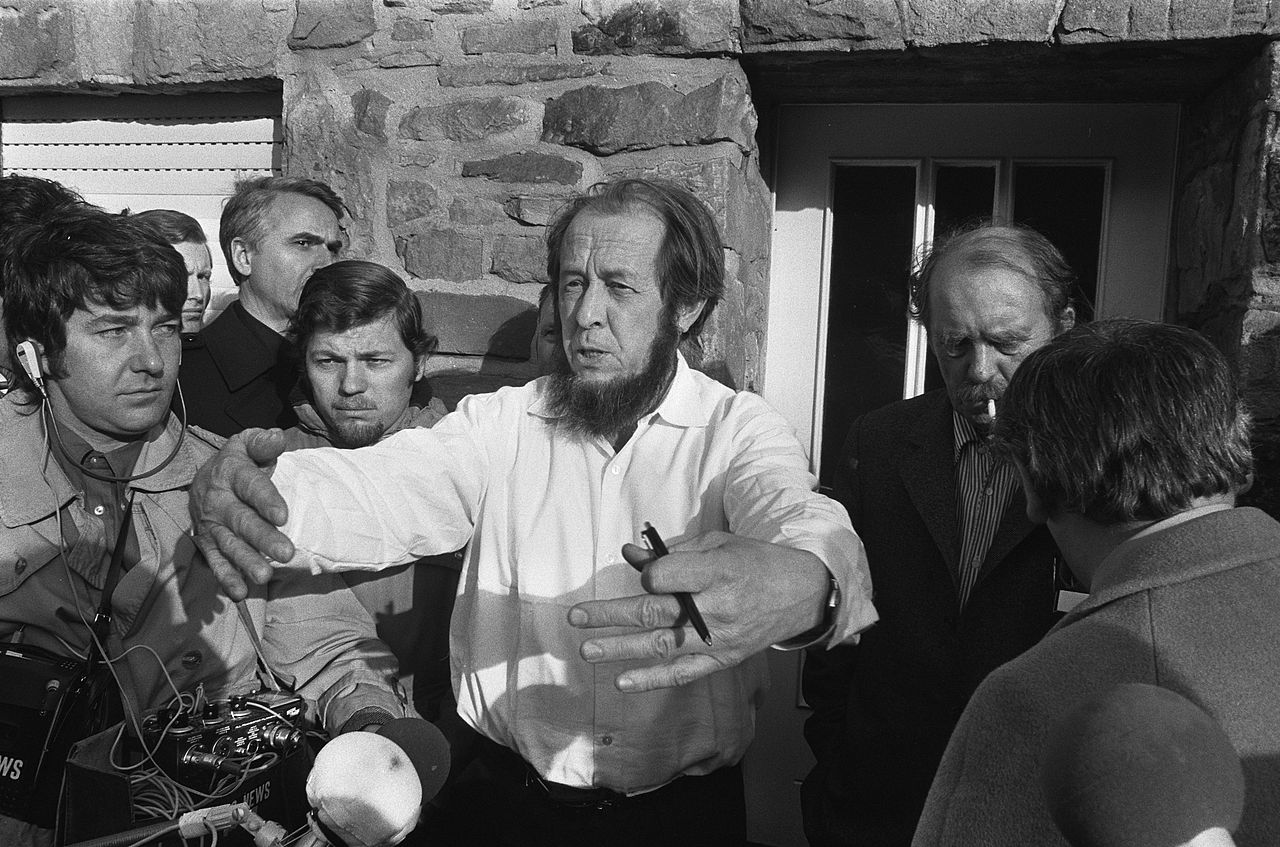

Solzhenitsyn addresses journalists in Cologne, Germany, following his expulsion from the Soviet Union. Photo: Verhoeff, Bert, Dutch National Archives

From Denisovich to Archipelago

In 1962, Solzhenitsyn published One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in the literary journal Novy Mir. The short novel described in fine detail the cold, grinding, hungry life of a Russian peasant in a Soviet labor camp.

“Alexander Tvardovsky, the editor of Novy Mir, was a very liberal man,” says Michael Scammell, a biographer of Solzhenitsyn. “When he saw this story, he realized that it was probably possible to publish it because there was no overt criticism of the gulag in the novel. It was simply the description of the life of one person in the camp. But of course, the message was in the actual life he described.

Solzhenitsyn’s description was drawn largely from his own memory of life in the camps, although it contained a nod to Soviet class considerations. “He transposed a certain period of his own life onto the life of a peasant, which he knew, for political reasons, would be a much more acceptable narrator than an intellectual would be,” Scammell says. “That coincided with the ideology that the state was a workers’ state run by workers and for workers.”

Khrushchev himself gave the book the green light, although more conservative figures in the communist system were not pleased.

“Domestic reaction was one of incredulity,” Scammell says. “There was astonishment that the topic could be addressed at all. After it was published, conformist, party-endorsed editors were complaining that they had been flooded with manuscripts by people who had been in the gulag who were now writing stories and novels about their own experiences.”

But whereas One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich had tested the limits of what could be published in the Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn had already begun work on other, more subversive works about the Soviet prison system.

There was Cancer Ward, based partly on his experience as a cancer patient while living in exile in internal exile in Kazakhstan, which he would attempt to publish without success.

There was In the First Circle, a novel about scientists and academics imprisoned in a more privileged part of the camp system, which he would fail to publish even in a self-censored version.

Both novels would be published abroad in 1968.

But throughout the decade, he was also laboring on a more cherished, more dangerous project that he had begun in secret in the late 1950s: A three-volume masterpiece called The Gulag Archipelago.

The Secret Book

The notoriety Solzhenitsyn had won from One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich made him the man to talk to about the gulag. And people wanted to talk.

“In the late 1950s, before his breakthrough, Solzhenitsyn had thought it was impossible to do what he wanted to do,” says Michael Nicolson of Oxford University, a long-time researcher on Solzhenitsyn.

“After One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, he was sufficiently well known, and sufficiently protected by his reputation, that he could go around freely and see people who gave him their memoirs and other information.”

He was also inundated with letters. “A huge number of them were simply expressing gratitude for what he had done,” Scammell says. “They were saying, ‘we have gone from being non-persons to persons.’ They praised the unsparing way he described life in the gulag. Many of them volunteered their experiences and he was able to correspond with them and ask specific questions.”

Solzhenitsyn also had numerous sources in Soviet publishing, including writers and editors who quietly opposed the Soviet system.

Unlike his other works, the Gulag Archipelago would not be a work of fiction, but a genre-defying blend of history, memoir, and reportage.

“One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich had been a one-off experiment to see what one could show by presenting something ordinary and unsensational,” Nicolson says. “But the Gulag Archipelago was a different proposition, since it was going to look at the whole history. It had to be done furtively. In fact, during the early 60s, he was writing Cancer Ward — which he believed he could have [had] confiscated without sending him to prison — on the surface of his desk and writing Gulag Archipelago ‘under the counter.’”

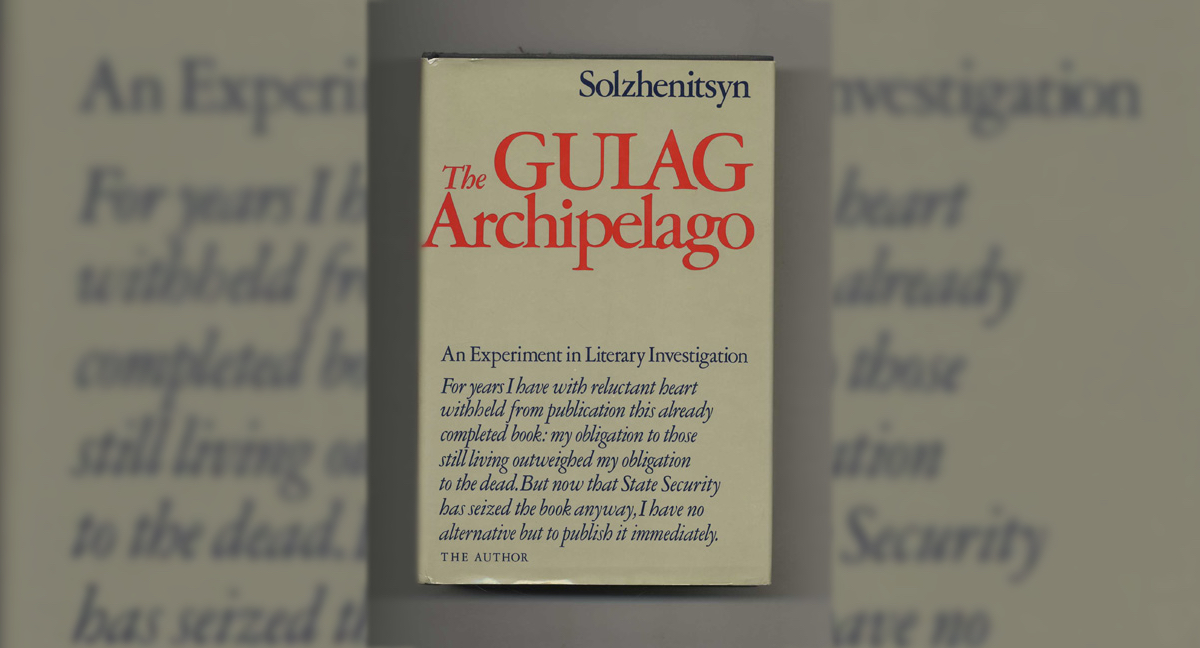

The first edition of the Gulag Archipelago, which appeared in 1973, carried Solzhenitsyn's explanation for releasing the book despite the consequences

So sensitive was the project that Solzhenitsyn never kept all his manuscripts in one place. The logistics of researching and writing the book presented significant challenges, as did the sheer scale of the subject. “He was trying to present very large slabs of unknown history, but [he had to deal with] elements of error and myth mixed up with other things, because much of the material had filtered out second and third-hand,” Nicholson says.

In some ways, the task was akin to one a well-resourced investigative journalist might take up in a more open society. “There is an element of trying to dig out the truth, which was not easy to come by. The circumstances under which he was working and the shortage of available published material meant that he was interviewing people. He refers to 220 or so people as ‘witnesses.’”

In other ways, it was not like a work of journalism at all. “There is a very strong confessional element, a thread of autobiography in the work,” Nicolson says. “He was coming to terms with the person he had been. He had an urge to try as many different slants and angles as he could, from the sober and forensic to the emotive and personal. This worked extraordinarily well in his favor.”

Solzhenitsyn ultimately subtitled The Gulag Archipelago “An Experiment in Literary Investigation.” At nearly 2000 pages of fine print, it covered the legal and political history of the gulag, Solzhenitsyn’s own arrest and interrogation, Solzhenitsyn’s moral reckoning with himself, and detailed chapters on such specific topics as women in the gulag, loyal communists in the gulag, methods of punishment in the gulag, and escapes and uprisings in the gulag.

But it was not clear how he would survive the ordeal of publishing it.

A Celebrity From the Gulag

The late 1960s brought darkening prospects at home. Khrushchev had been ousted from power in 1964 and the “thaw,” with its atmosphere of de-Stalinization and limited openness, was over. Trials and harsh sentences for writers deemed “anti-Soviet” were becoming a regular occurrence. Cancer Ward and In the First Circle had proved unpublishable in the Soviet Union. Solzhenitsyn was much admired both at home and abroad, but his popularity abroad was making his situation at home increasingly perilous.

Solzhenitsyn undergoes a body search in the gulag

In November 1969, the Soviet Writers Union — which determined who could and could not publish their work — expelled Solzhenitsyn. In its statement, the union wrote,

As is well known in recent years the name and works of A Solzhenitsyn have been actively used as propaganda for a campaign of slander against our country. However, A Solzhenitsyn has not only not publicly stated his attitude towards this campaign, but regardless of the criticism of the Soviet public and repeated recommendations of the Soviet Writers Union has, by a number of his actions and statements, in essence promoted the exaggeration of the anti-Soviet sensation surrounding his name.

But by this stage, Solzhenitsyn’s literary reputation was indestructible.

In 1970, the Nobel Committee awarded Solzhenitsyn the Nobel Prize in Literature, acknowledging “the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature.”

The prize was a public relations disaster for the Soviet Union. “It was a huge event,” Scammell says. “It confirmed Solzhenitsyn’s fame, which was already pretty great. The Soviet Union had already accepted the Nobel Prize as a legitimate international accolade, because when the Russian writer Mikhail Sholokhov had won in 1965, they had celebrated enormously. They could hardly say the Nobel Committee was biased or illegitimate.”

And while Solzhenitsyn was not able to leave the Soviet Union to receive the prize — he feared he would not be allowed back into the country — the publicity surrounding it proved useful. “It gave him a certain amount of protection because he was being constantly approached by journalists and watched by journalists,” Scammell says. “He also had literary and journalistic connections in the West which he could tap, either by picking up the phone or by sending a message via friends or intermediaries in West Germany, France, the United States, and Britain.”

The Soviet authorities, who had got wind of Solzhenitsyn’s cherished secret project, were determined to gain control.

In 1973, the KGB began locating and seizing Solzhenitsyn’s hidden manuscripts of the Gulag Archipelago. They also arrested and interrogated his typist, Elizaveta Voronanskaya, who hanged herself shortly afterward.

But Solzhenitsyn was prepared. He had arranged to have copies of the book smuggled out of the country on microfilm, and signalled his allies in New York and Paris to publish the book. The first edition carried a message from Solzhenitsyn on the cover:

For years I have with reluctant heart withheld from publication this already completed book: My obligation to the living outweighed my obligation to the dead. But now that State Security has seized the book anyway, I have no alternative but to publish it immediately.

Then, in February 1974, the KGB came for him. He did not know what would happen to him. According to his son Ignat, speaking to the TV program The Human Parade in 2014,

He knew it was coming…he expected that anything could happen. The most likely scenario, he thought, was another stint in prison camps and labor camps, although he considered the possibility he would be executed, he considered the possibility that he would be in solitary confinement, and also the possibility that he would be expelled.

His captors, it turned out, had picked the latter option. The authorities deprived Solzhenitsyn of his Soviet citizenship and, without telling him where he was being taken, put him on a plane and delivered him to West Germany.

But by that time, the damage had already been done. “It had a tremendous effect, Scammell says. “It was irrefutable. No one succeeded in delegitimizing it. Attempts were made inside the Soviet Union to try and pretend that it was invented, that it was untrue. But the best that even loyal Soviet Party members could do was try to explain it away and say, ‘well, all this was a byproduct of the time, and that at that time, there were so many ‘Enemies of the People’ that it was justified.’ It really blew a big hole in the official ideology.”

And while subsequent revelations from Soviet archives have allowed historians to correct the details, dates and statistics Solzhenitsyn missed while laboring in secret in a closed society, the book remains a haunting evocation of an era.

“Writing it was an enormous achievement,” Scammell says. “It is a unique work, and a great work of literature.”