News

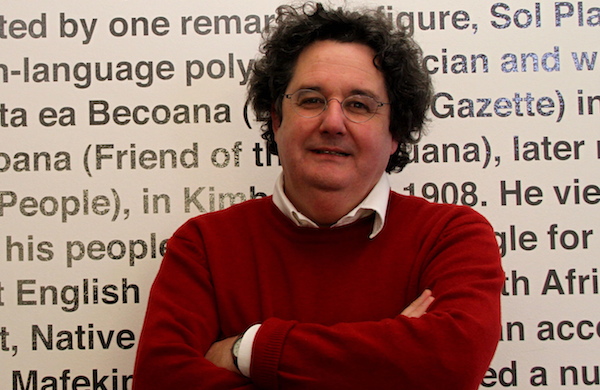

As an anti-apartheid journalist in South Africa in the 1980s, Anton Harber was constantly faced with threats of prosecution, imprisonment and restrictions. Still, he felt it was his obligation to push the boundaries of the strict State of Emergency laws and find alternative ways to tell the true story of apartheid.

“It was a very difficult time to be a journalist,” says Harber. “There were times where we were very afraid.”

Harber, who is today Professor of Journalism and Media Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, started his career as a reporter in 1980.

In 1985, at the height of widespread resistance to apartheid, he founded the Weekly Mail (now the Mail & Guardian) together with a small group of journalists. It came to be one of the most prominent anti-apartheid papers in South Africa.

How did censorship work during apartheid?

There were lots of laws about what you could and couldn’t do. When the Weekly Mail was four months old [in 1985], the government declared a State of Emergency, which had very strict media regulations that controlled what you could and couldn’t write about. If you broke those laws you would be subject to prosecution, arrest or detention. We often had editions of the newspaper confiscated and journalists were detained for long periods of time.

But the authorities also acted extra-legally, and that might be the most frightening thing. Journalists were subject to physical attacks, their houses were attacked, and there were attempts to kill journalists. So there were legal and extralegal actions, all of which together made it a nerve-racking atmosphere to work in as a journalist.

As the editor of the Weekly Mail, which took an outspoken anti-apartheid stance, how were you under pressure from the government?

I was fortunate that I was never detained, but I was prosecuted many times. Prosecution was one of the main weapons. It made our lives very difficult because it would tie us up in court, cost us a lot of money and make it difficult for us to work. If you had a few of those going at one time, it was obviously a huge burden. And of course there was a high risk of prosecution because you could get a jail sentence.

What were you not allowed to report on?

The kind of reporting that was most restricted was coverage of the security forces. With the uprisings the security forces moved into the townships, but the authorities banned us from reporting on anything they did without permission. And we couldn’t report on anyone detained under the State of Emergency without official confirmation.

But because there was some space in which we could operate, we were always testing the limits of what we could do. So we looked for grey areas of the law. The regulations were often very vague and broad, and it meant that you could interpret it in different ways. So we worked very closely with lawyers to find ways to say things without breaking the law.

Could you give me some examples on how you got around the laws?

Very often you had to read between the lines of what we were saying. For example, we weren’t allowed to cover security force action in the townships, so instead we would say somebody’s house was raided and someone was arrested “by unidentified people”. We sometimes pretended to be naive.

Another time we got a photograph of security force action in the township, and instead of publishing the photograph, we got an artist to do a “join-the-dots” drawing of it. We told people not to join the dots, because they would then get an illegal picture. Of course everyone joined the dots.

We weren’t allowed to publish any photos of Nelson Mandela, because he was in prison. So we hired an artist who sat with Mandela’s family, who described how Mandela had aged and changed, and the artist drew a likeness of him. We were able to run it because it wasn’t a photograph.

We also very boldly sometimes blacked out what we couldn’t write and publish. One week we did a whole edition of the newspaper pretending there was no censorship. When we were finished, our lawyers would go through it and tell us what was illegal, and we would put black lines over it, or black out pictures. The audience could then get a sense of how much they couldn’t know, in a very strong visual way. And the authorities couldn’t do anything because we censored the newspaper ourselves.

In that way we would see a gap in the law, and we would take advantage of it. Sometimes we would get away with it; sometimes they would prosecute us because we had gone too far.

A lot of newspapers were closed by the government at that time. The Weekly Mail was banned for one month in 1988. Why didn’t the government shut you completely down?

They closed us for a period of time, but they never stopped us from publishing completely, I think mainly because of international pressure. What kept us going, what kept us alive and what restrained the government from closing us down and arresting us all, was international pressure. They wanted the world to believe they still had a free press even though they didn’t. And don’t forget it was a period in which sanctions were introduced against South Africa. Closing us down would have just brought more sanctions. So that gave us protection.

And luckily we had a lot of supporters. Many of the best lawyers would defend us for no charge at all. We also worked very hard to build an international network, so when the South African authorities took action against us, we would make one phone call to someone in London, and it then went out to editors and diplomats around the world very quickly, and all of them would issue some kind of protest. That would help. It wouldn’t stop them but it would make them think twice about what they were doing.

You were prosecuted many times, but never detained. Why were you more fortunate than other journalist?

I had built a high international profile and network. And I suppose I also had more freedom because I am white. My white skin gave me more protection than a black journalist got. Therefore I felt it was my obligation to use that privileged position and the skills I had as a journalist to oppose apartheid as much as possible and do what I could to bring about its downfall.

How was the transition to democracy?

When they released Nelson Mandela [in 1990], all the prosecutions and laws fell away. Suddenly, overnight, we were free as journalists. And the truth is we were in total shock because we didn’t know what to do. We had to go through an enormous transition to become normal journalists as the society became a more normal society.

Under apartheid there were good guys and bad guys. It was simple. In a normal society things are more complicated. It’s not black and white. You have to do journalism of greater depth and balance. We were trying to relearn how to be normal journalists. It took about two years for us to find our voice again.

Other interviews from the Journalism is Not a Crime series:

“It was a question of surviving one day to the next”

Self-censorship is Extremely Hard to Shake off

Arrest, Torture, Exile: Journalism Under Military Rule in Chile

"I could hear my wife being tortured in the next cell"

Solidarity and the Underground Press

The Unwritten Laws of Argentina’s Dictatorship