News

Censorship became a fact of life for art and culture in Iran with the 1979 Islamic Revolution and many artists and writers were sacrificed to the repression of the freedom of expression. Many were forced to leave Iran – those who were forced to stay were also forced to censor themselves to support the new Islamic Republic’s ideology.

Censorship evolves every day to find new ways to harass theater artists – often provoking them to protest at their treatment. One of the most famous of these cases is the years-long harassment of Hamid Samandarian, a well-known theater director and writer, forcing him to take a job as a restaurant manager in protest at the ban on his production of Bertolt Brecht's play on Galileo, which he had also translated.

Bahram Beizai, a famous Iranian director and playwright, had similar experienced to which he referred in a letter in 1992: "I will break my hand and I will not allow you to force me to censor myself,” He finally was forced to leave Iran after constant censorships of his plays, stage performances and films.

Last year, in May 2020, 250 theater artists wrote a letter to the Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance of President Hassan Rouhani's government, protesting against the requirement for a new license from the Cinema Organization of the Ministry to broadcast their productions online. They said: "Why should a theater that was once licensed by the Center for the Performing Arts be licensed again by the Home Theater Network and be need to be reviewed again?"

In addition to censorship of ready-to-play theaters, censorship of ready-to-publish plays has also occurred frequently in recent decades, with many plays either left in warehouses and printing presses, or whose authors were forced to publish them illegally or by publications outside Iran.

Performances are not the only aspects of the theater to be censored. Published plays themselves have been repressed; many copies of plays have been left unsold, and some unpublished, forcing authors to publish and distribute them as samizdat texts or to submit them for publication outside Iran.

Censorship is Dirty and Inhumane

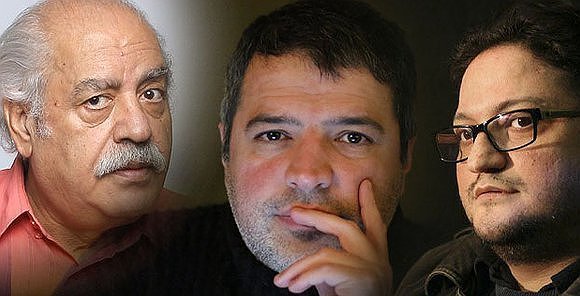

Behzad Farahani called government censorship "dirty" and "inhumane" and said it destroys the nature and spirit of a work of art.

"Censorship is prohibited in the country's Constitution, but we see that government censorships have become more severe in recent years, and for example, theater censors have become even more effective in their work. They are now aware of how playwrights and directors circumvent censorship, and they censor anything which is against their ideology or policies. The problem is that these censors, and the higher authorities who order censorship, have no understanding of the drama and do not understand they are destroying the rhythm and character of the work by fragmenting and trimming the play."

Farahani added: "The main issues for censors are moral issues and they want to prevent the development of social norms and morals that are against the government’s will. But these are Illusions. In this age, people think and live as they please, and the result of censorship has only been the destruction of the theater. Compare the type of women's hijab on the streets with the type of mandatory hijab imposed on female actors in theater and television. The actors seem to belong to 30 years ago, which is far from today's reality."

Farahani also pointed to the lack of connection between Shia Islamic jurisprudence, as well as the rulings of religious scholars, and contemporary attitudes and beliefs.

"Unless the Shia jurisprudence and the opinions of respected scholars align with modern understandings of life, we cannot expect any fundamental changes in the production of art and freedom of expression and thought. This has been the case for 42 years, and there will be no change for another 42 years. Censorship is dirty and inhumane and it that destroys the nature and spirit of a work of art. For example, in theater, the censors first read the play and censor it, then they review the work before a performance, when yet more censorship is applied; in the next stage, during the public performance, they are present in the hall to see how the audience reacts, when they laugh or cheer, to make sure these can be removed. Is anything left?"

Censors Deny Writers the Chance to Defend Their Work

Rouzbeh Hosseini, another playwright and director, said Iranian theater will continue to be harmed until there is a healthy and frank dialogue between writers and censors in which writers are able to defend their works.

Hosseini said: “There are two important issues for censors: one is erotic issues and the other is insults to the country's political figures. Other than these, there should be no problems, though in reality there are still problems. Every [censor] has a personal interpretation of language and this leads to the censorship of taste. And as long as the author's relationship with the reviewer is such that the censor writes a letter asking writers to delete a section, and then the writer tries to defend that section in a reply, this system will not work. Censors must call the author and hear their explanation – and they must be open to being convinced. The next important point is that writers should not self-censor, or express problematic matters under cover, or through indirect gestures. Writers should have the courage to express an opinion – otherwise it is better not to worry about it at all.”

Hosseini added that he is familiar with Iran’s frameworks and red lines in which he operates and does not seek to show off himself or chant vulgar slogans, but seeks to express his views directly and without censorship.

Hosseini also said: “For example, I do not like the fact that some writers, in order to express their opinion, shift the setting of their works from the current time to the period before the Revolution. This is a betrayal of writing. I waited 20 years to get permission to publish the second and third collections of my poems so that I could publish them with as little censorship as possible. When I know that I have to submit a text to the Ministry of Culture and Guidance of the Islamic Republic, then I have accepted a series of rules and red lines, but these red lines must be the ones approved by the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution and nothing more. I do not agree at all with some friends who, taking an intellectual stance, say that censorship creates creativity. Censorship destroys the text and the work and is the greatest betrayal of art.”

he went on to describe some cases of censorship of his works “It was in late 2001 that [censors] got stuck in the text of my play and closed my theater in the middle of a performance due to their own misunderstandings. They never told me to correct a part of the play or to not say such and such word; just that that the whole thing was banned. So there is no room for any right to defend the work. You have to be silent. And before giving permission to publish my latest collection of plays, by Afraz Publications, they objected to parts of one of my plays. I decided to remove the entire play from the book because I saw the text was seriously damaged and I did not want my work to be damaged. But I published the same play in Norway. I did not yield to the burden of censorship. I say that the fight against censorship is formed inside the artist at first and that you should not censor yourself."

Drain the Poison to Avoid Trouble

Writer, theater director and publisher Tinoush Nazmajou, who lives in Paris, said the scale and strength of censorship in Iran depends on the government and the minister in charge, and that censorship is sometimes stricter and sometimes softer. But he added that there is always censorship and it is unlikely to disappear until the final day of the Islamic Republic.

“In publishing, we sometimes thought that, for example, with a moderate and reformist government, the space may be more open. But the opposite was true. The same officials were more strict because they did not have the authority to act, for fear of the security agencies,” Nazmjoo said. “And within the Performing Arts Review Board there were employees who understood the meaning of the texts, and were familiar with literature, which made it harder to circumvent censorship and tacitly convey meaning to audiences. For example, in Mr. Ahmadinejad's government, when more illiterate officials were in charge, their understanding of the texts was usually lower and sometimes we were surprised that some plays received a license."

Nazmjoo’s works have been staged in Paris and he has also collaborated in non-Iranian plays. He established the the Nakoja (Nowhere) publishing house in Paris several years ago to translate and publish works that are unpublished in Iran due to censorship.

He added that, during his stay in Iran, censors in the Performing Arts Department asked him to take out the "poison" of a text so as not to cause trouble. In his opinion, however, a work of art that has no poison; work without criticism or creativity is worthless.

"Right now, censorship has no effect on preventing artists' works and ideas from being conveyed to the public," he added. "With the Internet and satellite TV, is it possible to hide anything anymore? People have access to all uncensored texts, films, and music, and the continuation of government censorships of theaters and cinemas has only reduced the quality of artistic production in Iran and shrunk their audiences. People are not obliged to consume only government-approved works like 10 years ago. Now the theater is almost dead in Iran and no good theater is produced because censorship has reached its peak. Artists working in Iranian theater have no choice but to unite to protest censorship and put aside their fears – in such an atmosphere they will not be able to compete with the other arts and to attract audiences."