News

The Iranian government harasses, imprisons and tortures journalists on a daily basis. Why? For exercising their fundamental right to freedom of information and expression.

Journalism is not a Crime was set up to support these jailed journalists. The site documents cases where journalists are unfairly arrested, and aids reporters and their loved ones by providing legal and psychological help to those affected.

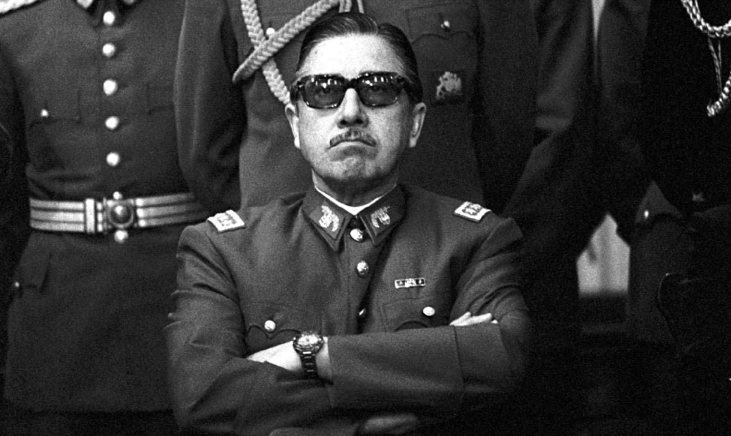

As part of the launch of the Journalism is Not A Crime campaign, Gideon Long spoke to Odette Magnet, who worked as a journalist under General Pinochet’s regime. Thousands of people were killed or forcefully disappeared during Pinochet’s rule, and censorship was practiced on a daily basis. Odette Magnet spoke about intimidation, the red mark of censors, and what it means to be a journalist.

Where were you at the time of the coup and where were you between 1973 and 1990? Did you spend the years of the dictatorship in Chile? In exile? Were you working as a journalist? For which news organizations?

I was 17 at the time of the coup in Chile. That year I graduated from high school. When we recovered democracy in 1990 I was 34. I never left the country. I had spent half of my life under a fierce dictatorship that changed my life, and the lives of millions of Chileans, forever. I studied journalism at the Catholic University of Chile from 1974 to 1977 under very harsh conditions: no freedom of speech, fear of speaking out in classrooms, classmates that worked for the secret police, censorship, right wing teachers. I learned very little and wanted to leave the place as soon as possible. In my least year of college I joined the team of Hoy because I had to do a three-month internship to get my degree. Hoy was the main Chilean magazine that opposed Pinochet. The best Chilean journalists were there under the leadership of Emilio Filippi, a remarkable journalist. I stayed for 10 years! They were amazing years that shaped my life and my understanding of what true journalism is: a sense of deep commitment to democracy and freedom of speech. A year earlier, my older sister María Cecilia and her husband, an Argentinian doctor, disappeared in Buenos Aires, victims of the dictatorship there.

How did censorship work in Chile during the Pinochet period? What kind of publications or broadcasts were censored? What was your own experience of censorship in the period?

By 1978 I was writing almost exclusively on human rights abuses: the disappeared, the tortured, the kidnapped, the exiled, the youngsters who were burned alive (Carmen Gloria Quintana and Rodrigo Rojas De Negri), the 1985 case of three communists whose throats were slit because of their political views, and so on and so on. There was not one week that we had nothing to write about. Every democratic publication that opposed the Pinochet dictatorship was censored: the three main radio stations (Cooperativa, Santiago and Chilena) were censored and shut down many times, as were we. Of course, at Hoy we faced fierce censorship. We were forced to send the whole magazine (including the adverts!) to DINACOS, a government bureau whose only purpose was censorship. They had 48 hours to go through all the material and highlight in red ink what was not allowed (they gave no reason). And then we had to send someone over to DINACOS to pick up the material, read what was banned and send a second “lighter” version. Human rights stories were a real threat, a Molotov cocktail! We learned to write between the lines and the readers learned to read the same way. But it wasn’t only human rights stories that were dangerous. So were articles on the economy, political issues, international affairs and anything that smelled like it could be “a threat to homeland security,” “antipatriotic” or about “terrorists and communists.”

How did journalists get around censorship? How often did journalists or activists get caught?

We were not caught. They harassed us, mainly. Our phones were tapped, they followed us, they took pictures of us in the street, sent us anonymous notes or letters threatening us, phone calls saying they would kill us. My colleague Patricia Verdugo received strange packages many times. Once she opened a box and there was a dead fish inside it, another time a pig’s head. They could have killed us at any time but they chose to force us to live in fear. I wrote about “The Degollados Case” (“The Case of the Slit Throats” in 1985) for a year. I never stopped. That was the worst year. They called me almost every night. I would pick up the phone and I could hear the sound of a typewriter and in the background, gunshots. Nothing else. No one spoke. I would listen and hang up but I always picked up the phone. And I would wet my bed sheets. And I forced myself to sleep, knowing that tomorrow would be another long day.

Were you ever arrested or imprisoned for your journalism? Did you know any journalists who were imprisoned under Pinochet?

I was never arrested and placed behind bars but I was detained for some hours once during a raid. Another time, a car with no license plates and no lights on parked in front of my house at night. Two men rang my doorbell and told me to open the gate. I didn’t. One of them reached inside his jacket as if he was going to take out a gun. I ran back inside the house. They just wanted to let me know that they were there, watching me. Many journalists were arrested and held for hours or days because of the stories they wrote. They were tried by military courts.

Can you give a sense of what it was like as Chile emerged from the Pinochet period? How long did it take for journalists to feel confident and to work as they wished?

For me and for many journalists it was like emerging from a tunnel and seeing the sunlight again, or waking up after a long and horrible nightmare. The 1988 plebiscite on Pinochet’s rule was key. For the very first time we sensed change, that the dictatorship was coming to an end after years of struggle. We were tired but we were hopeful that democracy was just around the corner. It was a slow process, there was still a lot of fear in the country, many scars needed to be healed, many families were suffering, unwilling to forget or forgive. Then came the 1989 elections. We slowly recovered an imperfect democracy and, particularly during the first year (1990-1991) the military was very vigilant and menacing. It was like they were saying “we are watching, we are not going anywhere.” During those years democratic Chilean journalists suffered self-censorship. It’s like a poison ivy that grows within you, silently, invisibly, and you fight it but it is still inside you. It took a long time to learn again to write with a free spirit, without fear or restrictions. It was not easy to emerge from the shadow of DINACOS and the red ink.

Can you say a little about how governments since 1990 have taken steps towards accountability and transparency? Has it been effective?

It took many years to recover the sense of being a free country again, a community, a sense of citizenship, with rights and duties. We had isolated ourselves not only from the world but among us there was a deep sense of mistrust and suspicion. I think we are still working through issues of accountability and transparency.

What do you feel is free about Chile’s media environment today? What is still restricted or taboo?

The main problem is the concentration of the media in the hands of a few. The media, basically, belongs to the same families. Apart from Chile’s most established newspaper El Mercurio and Copesa, which publishes its rival ‘La Tercera’ there is no democratic alternative.

Other interviews from the Journalism is Not a Crime series:

“During Apartheid International Support Kept Us Alive"

Solidarity and the Underground Press

The Unwritten Laws of Argentina’s Dictatorship

“It was a question of surviving one day to the next”

Self-censorship is Extremely Hard to Shake off

Arrest, Torture, Exile: Journalism Under Military Rule in Chile