Last Update

Feb. 26, 2021

Organisation

Unknown

Gender

Male

Ethnic Group

Azerbaijani

Religoius Group

Shia

Province

Tehran

Occupation

Journalist

Sentence

One year in prison

Status

In exile

Institution investigating

Ministry of Intelligence

Charges

Unknown

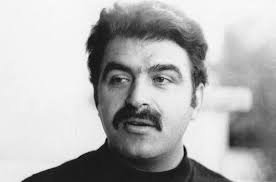

Gholam Hossein Saedi In exile

Gholam Hossein Saedi was an Iranian writer and journalist.

Saedi grew up during a politically tumultuous period, when Mohammad Mossadegh served as prime minister of Iran, and during the active movement to nationalize the Iranian oil industry and the subsequent 1953 coup d’etat (known as 28th Mordad) in Iran. It was during this time that Saedi began his medical studies and he also began to write his first novels and screenplays under the pen name of Gowhar Murad.

In 1962, Gholam Hossein Saedi left Tabriz and traveled to Tehran. This trip would mark the beginning of his acquaintance with a number of prominent contemporary Iranian thinkers and literary intellects. During this time, Saedi and his brother Akbar opened a medical clinic in the impoverished southern district of Tehran. Alongside his medical work, Saedi also contributed to literary publications such as Kitab Hafte/Book of the Week and Arash.

Saedi was one of the original founding members of the Iranian Writers’ Association, which was established in 1967.

However, in that same year, 1967, Saedi was arrested by agents from SAVAK, (the National Organization for Security and Intelligence, commonly known as the Pahlavi Shah’s secret police and intelligence service). He was subsequently transferred to Ghezel Qaleh Prison and then later to Evin Prison.

In a documentary about his life made by Shirin Saghaei, Saedi said that during his imprisonment he was continuously tortured in a solitary confinement cell over the course of a year.

After his release from prison, Gholam Hossein Saedi wrote two novels, Goor va Gahvareh (The Grave and The Cradle), Kalat-e Nan and the screenplay Afiyatgah. In 1978, Saedi was invited to the United States by the PEN America organization and during his time there he delivered a number of speeches. Saedi returned to Iran in the winter of 1978 just as the Islamic Revolution was unfolding.

Following the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Saedi was forced into compulsory exile against his will and in early 1982, he left Iran for Paris, France.

In one part of the documentary about his life, Gholam Hossein Saedi said: “It started with threats over the telephone. In the first few days after the Islamic Revolution in Iran, rather than writing novels and screenplays, which was my main form of work, I had to write articles for three major Iranian newspapers every day. There was one weekly newspaper, called Azadi, which was my main focus and responsibility. In each of the articles that I wrote, I confronted and opposed the Islamic regime. Before the suppression and crackdown on newspapers in Iran, after each of my articles was published, I received threatening telephone calls, so much so that during that time I had to leave my home and live a semi-secret life in an attic room for a year. Most members of the opposition who were in danger often came to me. We didn’t stay silent. We had secret publications and the regime’s agents went from door to door looking for me.”

Saedi continued: “Initially, they summoned my elderly father and said, ‘It was in Gholam Hossein’s [best] interest to report to the prosecutor’s office’. They constantly phoned my brother, who was a surgeon, and questioned him about me. They arrested and executed one of my close friends, who had spent the majority of his life in prison because he had fought against the Pahlavi Shah’s regime. One night, they [security agents] tried to storm into the attic I was living in, but before they could do so the woman who was living next door warned me and I managed to escape from the attic on the rooftops. I spent the whole night hiding behind the scenery decorations in a film studio. The next morning a few of my friends came to me, they combed my hair, shaved my mustache, changed my clothes and appearance so that I could go to a different hiding place.”

Saedi lived in a state of hiding and secrecy for about six months. It was during this time that he wrote more than a thousand pages of short stories. While he was in hiding, Iranian security forces arrested his brother.

Eventually, his friends were able to help him to flee from the country. “With tears in my eyes, anger in my heart, and through thousands of tricks and schemes, I was able to cross the border over the mountain and valley paths and arrive in Pakistan,” Saedi said. “Through the United Nations and with the help of a few French lawyers, I was able to get a French visa and travel to Paris.”

Between 1983 and 1986, Gholam Hossein Saedi continued to publish the Alefba magazine from Paris. He also wrote a number of other plays, screenplays and stories during this time. However, Saedi couldn’t bear life in exile. He died in Paris on November 23, 1985.

Gholam Hossein Saedi was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris close to the grave of Iranian writer Sadegh Hedayat.

For many years, Saedi published his works under the pseudonym Gowhar Murad. Speaking about his choice of pen name, Saedi said that behind his house in Tabriz there was an abandoned graveyard which he sometimes used to go walking. One day, while he was walking in the graveyard, he saw the grave of a girl by the name of Gowhar Murad who had died at a very young age. From then he decided to use her name as his pen name.

Gholam Hossein Saedi was of Turkish Azeri ethnicity and he had a deep interest in his mother tongue of Azeri. But in an interview with BBC Persian Radio, Saedi spoke about Persian as a language and its ability to create solidarity and national unity among all Iranians, saying: “The Persian language is the backbone of this great nation [Iran]. I want it to flourish. Regardless of whatever else is lost and destroyed, this language must remain.”