Last Update

May 2, 2021

Organisation

Iranian Writers’ Association

Gender

Male

Ethnic Group

Persian

Religoius Group

Shia

Province

Tehran

Occupation

Artist

Sentence

No sentence

Status

Released

Institution investigating

Ministry of Intelligence

Charges

Unknown

Date of Birth

20/11/1940

Place of Birth

Tehran

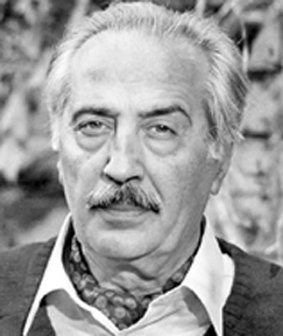

Mohammad Ali Sepanlou Released

Sepanlou's entry into the Iranian literary community, in 1963, came with the publication of "Oh ... Desert," which was his first collection of poems. Over the course of half a century, he has published more than 60 books of poetry, literary criticism and research.

Sepanlou was one of the first members of the Iranian Writers' Association. From the 1960s until his death, he was a constant and calm presence in the movement to achieve freedom of speech and other goals of the association.

The most important theme of Sepanlou's poems is Tehran, the capital of Iran and the birthplace of the poet. In all his poems, he more or less refers to Tehran, but in three collections, "Ms. Time," "Dark Figure" and "Boating in Tehran," Tehran is portrayed mythically. "Ms. Time" is the most well-known among these works.

Sepanlou wrote many other poetry collections including "Dirt,” “Thunderstorms,” “Sidewalks,” “The Absent Sindbad,” “Invasion,” “Pulse of My Homeland,” “Hour of Hope,” “Streets,” “Deserts,” “Firoozeh in the Dust,” “The Autumn on the Highway,” “Jaliziana”, and “Exile in Homeland."

Sepanlou was also among the writers and intellectuals who was target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt in 1996 in what became to be known as the "Armenian bus" incident.

The incident was part of the Chain Murders of Iran and took place on August 6, 1996. The Ministry of Intelligence in the government of then president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani intended to kill a large number of Iranian cultural figures and send them all to the bottom of a valley.

The opportunity arose when the Writers' Association of Armenia invited members of the Iranian Writers' Association to travel to Armenia for a three-day poetry and cultural conference. At the time, flights between Tehran and Yerevan took place only once a week and it was not possible for the travelers to stay for a week. The group therefore traveled by bus. Ghaffar Hosseini, a member of the Iranian Writers' Association, became suspicious at the time and expressed his concerns bluntly, saying that "They are going to send you all to the bottom of the valley," but others ignored him.

Twenty-one cultural figures, including Mohammad Ali Sepanlou, headed for Armenia on a bus driven by Khosrow Barati, who was later identified as an agent of the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence. According to Mansour Koushan, another passenger, close to dawn passengers realized that the bus had stopped at one of the turns and the driver was not behind the wheel. He was standing a small distance away outside the bus. He told them that he had fallen asleep, become afraid and disembarked the bus.

The writers then remembered Ghaffar Hosseini's prediction. Despite their strong fear, they decided to continue but to have two people sit near the driver to monitor him. After moving about four meters, the driver sped up, turned the bus towards the edge and jumped out of th vehicle. But the passenger Masoud Toofan immediately took the wheel and another passenger, Shahriar Mandanipour, pulled the handbrake to stop the bus at the edge of the abyss.

In a story published in the Aftab-e Emrooz newspaper on November 11, 1999, Masoud Toofan said that after the bus was stopped, the driver returned and claimed that he had gotten off to put a stone under the bus. The driver then sat behind the wheel again and repeated the same maneuver.

"I immediately jumped behind the wheel and turned it," said Toofan. "I did not dare to press the pedal under my foot, I did not know if it was the accelerator or the brake. Finally the bus stopped, one wheel hanging over the valley.”

According to Massoud Behnoud, a journalist on the bus, they then informed the police station near the scene of the accident, and the passengers were taken there. Then, Mostafa Kazemi, a famous interrogator at the Ministry of Intelligence, intervened and transferred all the passengers to Astara prison. There, the writers were released after being threatened and forced to commit to silence.

In another incident, in the fall of 1999, 17 Iranian political activists, intellectuals and writers were invited to "Iran after the General Elections," a conference in Berlin, Germany, planned for April 2000. Sepanlou, along with Mahmoud Dolatabadi and Moniro Ravanipour attended the conference, which later became known as the “Berlin Conference.”

During the conference, Sepanlou's poetry and storytelling session was canceled due the opposition of the audicance from a few political groups outside Iran, including members of the Mojahedin Organization, and he only answered questions.

Airing the footage of the conference on Islamic Republic TV caused an uproar among hardliners inside the country and a summons was sent to Sepanlou to appear in court upon his return to Iran. He went to court and was acquitted alongside Dolatabadi, Ravanipour and Jamileh Kadiver two months later.

In the years following this incident and until the end of his life, Sepanlou struggled with government censorship in Iran. Some of his works were not allowed to be published. He said at the time in an interview that he was upset about it and that he may give up writing.

"Sepanlou was one of the people who suffered from censorship," Mahmoud Falaki, a poet and novelist living in Germany, said of the censorship. “Some of his works were not published, and some collections that were published were licensed after removing some of his poems. This is the pain that all writers have to deal with, and Sepanlou suffered from it too. But as far as I know, Sepanlou continued to work until the end of his life. His work not receiving publishing permits did not stop him. He published some of his books abroad. It was an escape route that some writers, like Golshiri and Dolatabadi, found to publish the works they could not publish inside Iran. Sepanlou chose the same path. And we know that there must be works by him that have been written and have not yet been published."

Sepanlou suffered from lung cancer for several years and finally died on May 11, 2015 at the age of 75 in Sajjad Hospital in Tehran. He was buried in the Behesht-e Zahra cemetery in Tehran.

"The name of all the dead is Yahya" is one of the most famous poems of Sepanlou, which was inspired by rocket attacks on Iranian cities during the Iran-Iraq war in the winter of 1987.

Sepanlou also acted in films including "Tranquility in the Presence of Others," "Shenasayi," and "Rokhsareh."

"They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" "The Comedians," "Lockdown," "The Just Assassins," "Childhood of a Leader," "Corridor and Stairs," and "Guillaume Apollinaire in the Mirror of His Works" have been translated and published by Sepanlou.