Last Update

Nov. 30, 2020

Organisation

Unknown

Gender

Male

Ethnic Group

Persian

Religoius Group

Shia

Province

Tehran

Occupation

Journalist

Sentence

Eleven years imprisonment

Status

Killed

Institution investigating

Ministry of Intelligence

Charges

Acting against National Security

Espionage

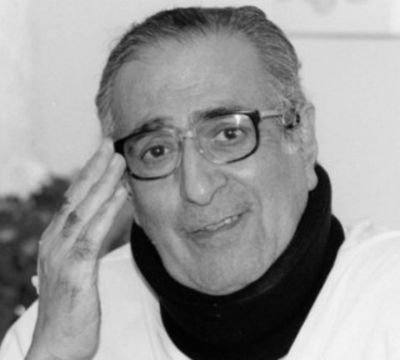

Siamak Pourzand Killed

Siamak Pourzand was a journalist and activist, born in Tehran in 1931, who died there on April 29, 2011, at the age of 80. He had been detained and tortured on several occasions times by the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Siamak Pourzand's father was a high-ranking soldier in Iran's military and an active supporter and player in Iran's 1905 Constitutional Revolution. Siamak Pourzand’s widow, Mehrangiz Kar, who lives in exile in the United States, is a writer, lawyer, and human rights and women's rights activist. Pourzand's mother and aunt spent their teenage years abroad, active in the arts, both as students and teachers and as performers.

Ahmad Shamloo, a famous Iranian poet and writer, was Siamak's cousin.

Siamak Pourzand graduated with a Masters degree in arts publishing and in 1952 he began his career in journalism with the Bakhtar Emrooz newspaper which was under the management of Hossein Fatemi. He worked at this newspaper as a researcher and reporter on urban and cultural/artistic affairs until August 19, 1953.

In the fall of 1954, Pourzand founded a weekly magazine called Peak Cinema, and he worked with a number of prominent Iranian writers such as Parviz Natel Khanlari, Saeed Nafisi, Ismail Mehrtash, Ali Asghar Garmsiri and many others who all contributed to the publication. And with the support of his cousin, the poet Ahmad Shamloo, Pourzand worked on the design and publication of the Kayhan Book of the Week periodical magazine. Pourzand took over its executive management, public relations and art section and was involved in the publication for several years until it was suspended and forcibly shut down.

Pourzand, along with several other journalists and writers, also played an important role in establishment and foundation of the Syndicate of Writers, Journalists, Translators and Photographers of Iran in 1960, the Syndicate of Artists and Theater and Cinema Specialists of Iran in 1961, and the Union Newspaper Sellers of Iran in 1961.

Pourzand was also an elected a member of the board of directors for the Syndicate of Writers of Iran.

Siamak Pourzand was a member of the editorial board and a member of the senior editorial board of Kayhan newspaper for more than 15 years.

After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Pourzand was forced to resign from his positions at Kayhan. He continued working with and contributing to a variety of publications and newspapers including the Cinema Report.

Arrest and Incessant Persecution

In April 2000, a conference in Berlin, Germany, titled “Iran after the Elections” and later known as the “Berlin Conference" – a three-day affair organized by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, an independent German cultural organization which, in collaboration with the German Green Party, hosted Iranian intellectuals and political activists to express their views on Iran's political and cultural issues during President Mohammad Khatami’s reformist government.

The conference itself was notable for the anti-government demonstrations by Iranian dissidents, which involved a number of protesters undressing in public and shouting chants against the Islamic Republic of Iran, which disrupted the gathering and gained widespread news coverage.

After returning to Iran, a number of conference participants were arrested and interrogated on charges of “committing actions against national security.” Among those arrested was Mehrangiz Kar, a criminal defense lawyer and Siamak Pourzand’s wife. In interviews she gave after later leaving Iran, Kar said that during her interrogations she had learned that her husband was under close surveillance by the Iranian security services. On the day of her trial, the representative of the prosecutor in her case spoke to Kar in private and said: “Soon, we will also severely punish your husband.”

But according to Kar, Pourzand did not believe this was the case and he did not believe he was in danger. At the time of the Berlin Conference, Siamak Pourzand was in Sweden and was unaware of his wife's attendance at the conference.

Kar also said that, during her interrogations, the investigator asked her to explain Pourzand’s involvement in the conference, asking: “How did Siamak Pourzand set up and organize the Berlin Conference?”

After the trial, Mehrangiz Kar asked her husband, who was in Sweden, to not return to Iran: “I begged him not to return, but he really wanted to support the reformists and returned to Iran.” He was arrested on his return to his homeland.

According to Mehrangiz Kar, Pourzand was arrested because of his support for the reformists in Iran. Kar states: “He was not a participant in the Berlin Conference, he didn’t even know anything about the Berlin Conference. He was accused of taking millions of dollars from the US government and distributing it among reformist media outlets.”

Kar also claimed there was no evidence to support the charges in Pourzand's legal case. She has said: “What [evidence] they had was a written confession in Siamak handwriting, the entirety of which was extracted from him under coercion and torture.”

Some analysts believe that the hardline pro-regime faction of the Islamic Republic had fabricated a legal case against Siamak Pourzand so that they could use him as a means of creating a conflict with the reformist movement and to undermine the “growth of Western culture” in Iran.

Accusations of Illicit Relations

One of the charges filed against Siamak Pourzand was “engaging in illicit relations." Mehrangiz Kar explained this charge, saying: “The manager of the cultural center where Pourzand worked sued him, claiming that Pourzand had engaged in illicit relations with her. The manager later told Pourzand's sister that she had been abducted twice and blackmailed into filing the legal complaint against Siamak Pourzand, claiming that they had engaged in illicit relations. According to this woman, they [the security services] had said: ‘If you do not sign this written legal complaint, we will stone you to death!’”

Eventually, after having endured several months in solitary confinement, Siamak Pourzand was sentenced to 11 years imprisonment in closed court hearings and without any form of legal representation.

Pourzand was also forced to make televised confessions in which he admitted to charges against him and confirmed a number of other charges filed against his friends while he was under coercion from his interrogators. He later testified that during his interrogations he confessed to “everything but murder.”

After having served some of his sentence, at the age of 71 and in deteriorating health, Pourzand was transferred to hospital to receive medical treatment. He was then transferred to his home, where he was kept under house arrest. But in March 2004, as part of a wider wave of arrests against writers and film critics, Pourzand was arrested once again and taken back to Evin Prison.

Ahmad Masjed-Jamei, then minister of culture and Islamic guidance, and the Iranian Writers' Association, protested this wave of arrests against Pourzand and a number of other writers and film critics.

But Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, then chief of Tehran's police and the current (2020 to ongoing) Speaker of Iran's parliament, responded to the criticism of the arrests by saying: “These individuals were engaged in spreading cultural obscenities and they formed an extensive distribution network of vulgar films, of which more than 13,000 vulgar and offensive CD discs have been discovered.”

Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf’s remarks were in reference to a number of foreign films that Pourzand owned, of which there were far fewer than Qalibaf claimed, which were not subject to the same censorship that is enforced by the Islamic Republic of Iran. Pourzand had collected these films so that he could write analyses and reviews of them for film magazines such as Film Report and World Cinema.

After serving part of his sentence in prison, Pourzand was transferred back to his home due to his old age and illness. He was kept under house arrest, under the supervision of security officers, and he was banned from leaving Iran. He became seriously ill. He was only released from prison after his family and several European governments wrote public letters in which they demanded his release. However, four months after his release, Judge Zafar Ghandi ordered that Pourzand be transferred back to Evin Prison. In 2004, Pourzand suffered a heart attack and was subsequently transferred to the intensive care unit of Modarres Hospital in Tehran.

Suicide

Due to his poor health and his old age, Siamak Pourzand was once again transferred from custody to his home where he was kept under house arrest.

Pourzand was prohibited from meeting his family who lived outside of Iran. Only once was Azadeh Pourzand, his youngest daughter, allowed to visit him in Iran, during which time she was able to spend 10 days with her father.

On April 29, 2011, Siamak Pourzand committed suicide by jumping from the balcony of his home.

At the time of his death, Lily Pourzand, the eldest daughter, told Radio Farda that her father had ended his life in protest against his house arrest and living conditions. Pourzand’s death was widely reported by both Iranian and international media.

In an interview, Mehrangiz Kar said: “On the morning of April 29, 2011, a man, who had just turned 80, threw himself to the street from the sixth floor of a building which everyone thought was his home, but which, in reality, was his prison. He had survived the oppression of the tyrants, but he could no longer tolerate waiting the short time left before his natural death in that prison. His name was Siamak Pourzand and he had a tumultuous life. His only crime was to reveal secrets. He thought long and hard, and many people knew he was right. This meant he was to become a fresh victim to be crushed in the clutches of those deranged men."